Notes from Order Without Design

Published 12 September 2024 ⋅ Comment on Substack

Back to writingContents (click to toggle)

3,868 words • 20 min read

(sidenote: Don’t judge books on their cover, yes. But are beautiful covers no guide to which books you should give your time?) It was great and my Goodreads review ballooned into the post you are reading.

Two thirds of this book is descriptive. It explains how modern cities grow and work — especially how housing prices and wages are set — from the perspective of urban economics.

I

Here’s the motivating question: why do cities grow? Since effectively all (sidenote: Say, population >500k.) cities are not de-novo construction projects but grow from smaller cities, and smaller cities typically grow from smaller settlements, we are really also asking: why are there cities?

After all, land is least expensive where it’s not already crowded with people. So if it’s land per dollar people are after, then we we should expect populations to be distributed more uniformly across space than they in fact are, as they increase.

For Bertaud, the most important explanation is that cities are labor markets. Employers and employees want to move to where they can find the best choice of employees and employers within their budgets. They’re willing to pay a premium to live where they can expect to find more suitable hires (employers) and jobs (employees). The solution is to go where everyone else is, and the result in aggregate is to concentrate population density: no functioning labor market, no city.

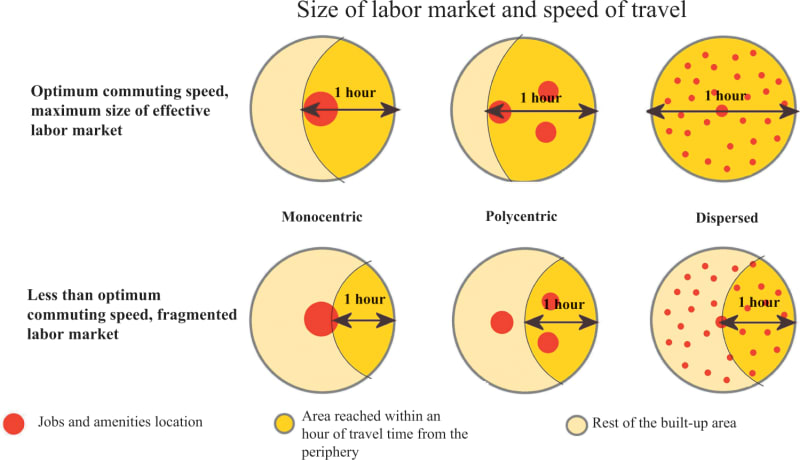

The effective size of a labor market is the average number of jobs reachable in a commute. So it can grow by increasing the distance reachable in a commute, or by becoming more dense (in terms of people per floor area and floor area per land). People seek out and benefit from larger labor markets.

Most cities operate in a market economy, where housing is (predominantly) a consumer product. Well-functioning markets use prices to allocate existing resources in a way that matches supply and demand. In the ideal case (when trade is free, transaction costs are low, goods are properly priced), this matching is (sidenote: That is, the quantity of housing supplied matches the quantity demanded at the market-clearing price: there’s no excess supply (empty homes) or excess demand (housing shortage) in the long run.). And if the supply of some product is flexible and competitive, prices eventually fall because more of the product is made. So it goes with housing (where housing markets are ‘well-functioning’).

The value of land is the discounted value of rents which can be taken from that land; from whichever use — residential, commercial, industrial — is most valued. Land itself can be productive (as in, farming) but that’s mostly moot as long as we’re considering land value in cities.

The end result of urbanisation is floor space, not land. In particular, floors can be stacked on top of one another to increase the ‘floor-area ratio’ (FAR) of a plot. Higher FAR values lower the cost of land per unit of floor space sold.

Imagine you’re a developer and you’ve just bought a plot of land in the central business district of a big city. People really want to live and work in this area, mostly because it’s near all the existing jobs. Since demand is high (and the supply of land is fixed), the land is expensive.

How many floors should you build? Regulations aside, the marginal cost of adding extra floors is basically the cost of construction, which is roughly the same anywhere in the same city. The high price of land reflects that the marginal revenue per floor area is high. So you can imagine it will start out cheaper to add the same floor area by building up, rather than horizontally (by acquiring more land). Assuming the marginal cost per floor increases as you build up, eventually building up is no longer economical. The price of land determines the height at which you stop adding floors; if you had bought land further away from a central district, you should stop at fewer floors.

In this way, density traces how dearly land is valued. “The decision to build tall buildings or short ones is therefore not a design choice left to a planner, an architect, or a developer. It is a financial decision based on the price of land”.

When the most valued use of a parcel of land changes, the current owner sees that they would do better by selling their land to make way for the more valued use. Declining uses make way for valued uses: yesterday it was meat packing plants and unloading docks making way for residential housing; today it’s more like half-derelict malls. In this way, markets shape cities through land prices, via changes in use and density.

Other parts of the city behave differently.

Roads and parking are improperly priced, because drivers do not pay their full social cost (from congestion, noise and pollution, and the opportunity cost of the land). If the negative externalities to roads are large, we should expect free roads and parking to be overused by default. Over-usage could be (sidenote: Get it?) if roads were properly priced to the consumers, such as through tolls. That applies to free parking space also (sometimes minimum parking area is a mandated requirement for commercial buildings).

Transport infrastructure (roads; but also bus networks, metros, etc.) effectively increases the size of a labour market, with large benefits. Since they are (semi-rival) public goods, typically private markets do not supply public transport, so public transport falls in the domain of city planning and administration, along with other city services. Large expenditure on transport infrastructure can be justified if it increases mobility (and e.g. reduces pollution, or frees up land from parking).

The picture in my head is of buildings and land uses as flowering plants, and transport infrastructure as the trellis needed to hold them together and cultivate their growth.

II

That was the first two thirds; the mostly descriptive parts. By the choice of emphasis (and Bertaud’s fondness for Hayek quotations) it’s not so hard to see where this is going.

The other third is polemic. It’s polemic against the presumptions and overreach of planning — of overbearing land use regulations, buzzword-driven zoning laws, poorly motivated limits on building height and city extent. The morass in which “a creative zoning lawyer is far more likely to increase the profitability of a future building than a creative architect or engineer”, based on neither theory nor empirics but simply the “need to do something”. Seeing Like a State City.

Angus Deaton wrote: “the need to do something tends to trump the need to understand what needs to be done. And without data, anyone who does anything is free to claim success.” Bertaud thinks this is what happens when planners, who are typically unfamiliar with urban economics, are given a very broad remit and face pressure to see “something done” to quickly fix salient problems like unaffordable housing.

Bertaud argues the policies that result — maximum heights, minimum parking lot sizes, minimum dwelling areas, urban growth boundaries, etc. — limit the supply of housing, and so make housing predictably more expensive. “All binding urban regulations increase the cost of housing—I insist: all binding regulations.” (sidenote: I can’t remember if Bertaud includes straightforward subsidies (like vouchers redeemable for rent) aimed at helping people who cannot afford any decent housing. I think we shouldn’t be counting these instruments since they are not binding on supply. Certainly the argument is not (or shouldn’t be) ‘government can’t or shouldn’t help make housing affordable’!), this is bad juju.

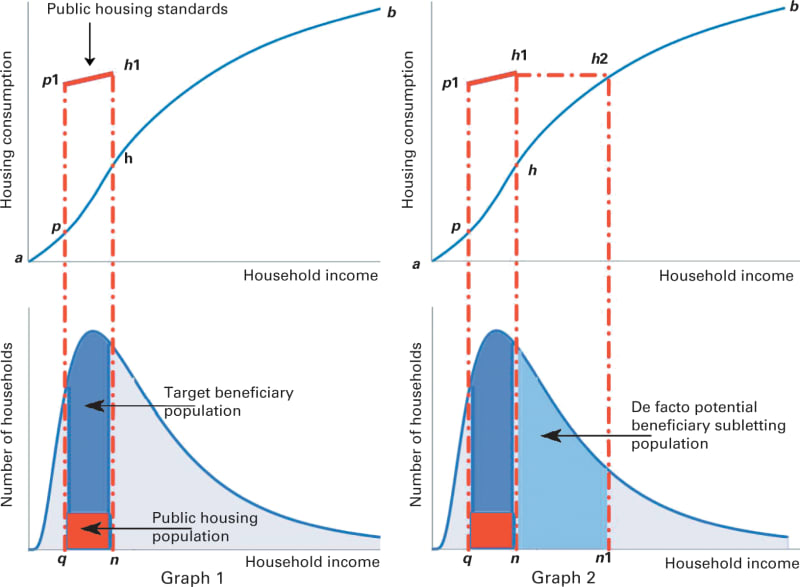

Take the (comparatively benign) example of mandated minimum standards of housing. These are well-intentioned rules designed to improve quality of living for low-income tenants by requiring that all housing units be rented or sold with a minimum floor space. Bertaud writes:

The regulations will not lift the poor out of poverty. However, the regulations will prevent the construction of the only type of housing poor households can afford. If some developers are ready to continue building housing below the minimum standard, these houses will become illegal, exposing poor households to expulsion or to demolition of the only type of house they can afford. Regulations fixing minimum housing consumption thus deprive poor households of property rights.

Bertaud considers a specific case study in the book, New York’s (2016) ‘inclusionary zoning’ strategy. On which:

[M]unicipal zoning ordinances [request] developers of housing projects above a certain size (usually above about 200 units) to provide from 20 to 30 percent of units at a price or rent fixed by the municipal government below market price and defined as affordable. For the rest of the units, the developer is free to use market prices or rents. Usually, as an incentive the municipal government gives the developer a development bonus in the form on an increase in FAR above the current one imposed by the zoning.

If you don’t think about it for too long, this sounds like a free lunch. The municipal government pays no direct cost to build earmarked affordable housing; rather it can conjure affordable housing by dangling FAR-limit to private developers.

But it fails in really sad, pernicious ways. Not nearly enough developers hold out fixed rent rooms to clear the market at the mandated price. So the rooms become a cruel lottery which most eligible entrants lose (and the poorest are ineligible for in the first place). Developers of luxury apartments took the incentive (since they can afford to), but then they segregated services and even entrances by the two kinds of tenant.

After that unintended consequence, the municipal planners mandated that the fixed-rate apartments be evenly mixed in with the market-rate (luxury) apartments, making it impossible to segregate access.

For similar reasons, lucky winners of the lottery were prohibited from subletting their properties, leaving them much worse off than if they could take rent instead and find a place more appropriate for their needs. The ideal was commendable — that low- and high-income tenants should enjoy the same high quality of housing. But the result (from preventing subletting) is deadweight loss: large losses and no winners.

There’s a pattern here which recurs in other case studies. You take a policy being devised to meet a good and important outcome, like making housing more affordable. Early pilots of the policy run into outcomes which offend the imagined outcome of the planner. So further mandates are introduced, to smooth out those irregularities. Soon the result is not just bad on cost-benefit grounds, but patronising to the intended beneficiaries. In retrospect, a much simpler policy could have worked better (like no-strings housing vouchers).

Instead, well-intentioned rules with unfortunate consequences often grow into a kind of thicket, introducing fixed costs to at all understand which kinds of new housing are in fact legal, and then to produce the necessary reports, which amount to thousands of pages. Bertaud’s prescription:

My guess is that any serious reformer should approach urban regulatory reform in the same way as a doctor develops a treatment for a drug addict: a progressive withdrawal planned over the long term.

And:

Regulations should be designed and tested with great caution, in the same way as what is required before a new drug is put on the market.

Bertaud’s second, more positive suggestion, is that city mayors and their municipal staff think of themselves as a kind of “well-coordinated team of competent managers and janitors”, as opposed to rulers or designers:

A city is entirely created by its citizens’ initiatives. These citizens are required to act within a set of “good neighbor” rules, and to be supported in their endeavors by a network of physical and social infrastructure managed by a mayor and a city council.

In the spirit of the late James Scott, so much of this book is really a call for modesty about the creative potential of planning alone:

Hewlett Packard and Apple were started in garages, in violation of local zoning laws! The deans and provosts of Stanford University had vision, as they encouraged their students and researchers to start their own enterprises, and provided start-up incubator workspaces on land belonging to the university. But no visionary mayors or urban planners were involved in the creation of Silicon Valley.

Nearer the end of the book Bertaud is at his most withering:

If [these policies] have such an obvious disastrous consequences for the poor, why do most urban planners continue to include them in their master plans? The only answer I can think of is planners’ propensity for utopia and their dislike for reality. A quotation from Albert Hirschman, “an oppression of the weak by the incompetent,” best illustrates this point.

Man, he really has it out for urban planning. But, if valid, I think this might be a useful a contribution from the book to Twitter-centric YIMBY tropes, which tend to pin blame on popular support for housing supply restrictions. If instead a specific profession can account for a large fraction of failures in urban planning, it might be more feasible to bring around its norms and attitudes.

III

Again, the book is not arguing that “planners and governments should stay out of our damn cities”. The best cities contain public goods, like publicly owned buildings, parks, and transport infrastructure.

So, what about the bull case for city planning? Can really great planning “transform” a city? Or is planning a necessity to be somehow minimised?

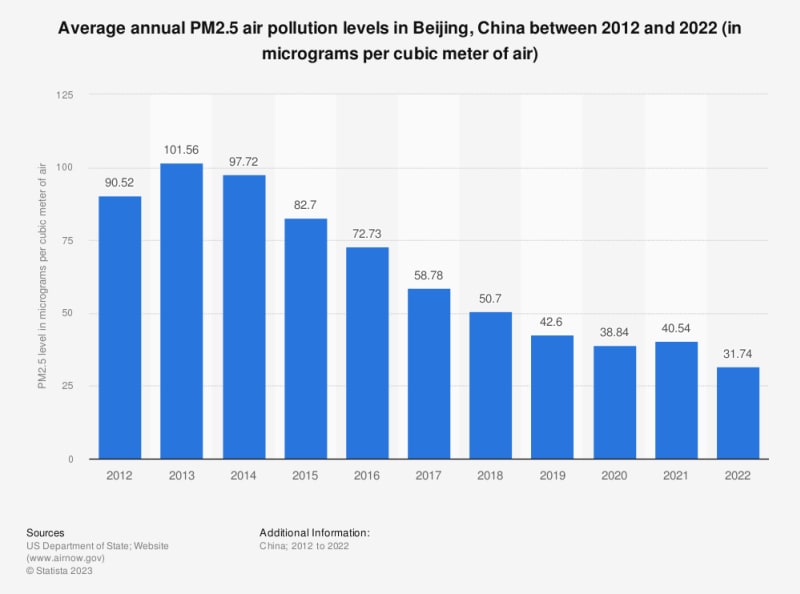

I think it’s fair to reject the question. The best gardeners don’t try to radically reform a garden year-on-year; they cultivate it through frequent and often unnoticed hard work. At least it’s worth distinguishing city planning (as in, building new projects and regulating land use) and municipal services (as I, running the city). Big new public works projects can overshadow the work of running and improving public services, but this is the vast majority of the work municipal governments do. The result is the unnoticed water we swim in: not just obvious things like waste disposal and emergency services and transit, but fire regulations and gas and electricity supply and monitoring and enforcing water and air quality! For example Beijing more than halved measures of smog and air pollution (PM 2.5) (sidenote:

And I think there are kinds of city planning where the returns to big-picture design truly are enormous. This is when cities are very new, but where very fast growth can be anticipated, especially in developing countries. In these cases, simply marking basic infrastructure — especially road networks — can provide the ‘trellis’ around which the newly emerging city grows. Again: basically all public transport needs to be planned, and mobility in a city is a huge deal!

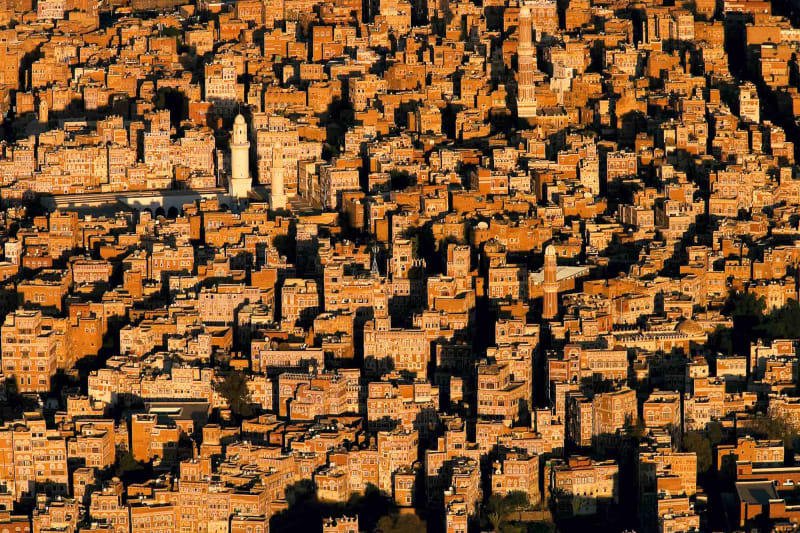

For instance: Bertaud was commissioned by the UNDP in the 70s to work for Government of Yemen and advise on how its capital, Sana’a, might be guided as it developed:

The civil war that gave rise to the Yemen Arab Republic had ended just 2 years before my arrival. During those 2 years, the country had begun to open to the outside world for the first time in its history, triggering a massive urbanization process.

In Sana’a, writes Bertaud, he would have to play the role of L’Enfant in planning DC, or Cerdà in Barcelona.

To have an impact, I would have to use the land itself as my drafting board, drawing streets directly on the ground with the agreement of the farmers and tribal chiefs who owned this land. […] My assistants then poured lime along the axis line. The landowners would then discuss the width of street. The wider the street, the more land they would lose; alternatively, they also understood that wide streets would enhance the value of their lots. After some discussion, we agreed on a width, and we drew two parallel lines that became the limits of the new street’s right-of-way.

I am convinced that tracing streets—the task of separating public space from private space in advance of urban development—was certainly the activity that had the highest rate of return for the urbanization of the city. Looking now at a Google Earth image of Sana’a, I can still see some of these streets, now asphalted and densely lined with buildings.

(sidenote: The authors looked at ‘sites and services’ projects in seven Tanzanian cities in the 70s and 80s, and compared areas that received preemptive basic infrastructure investment (like roads and road drainage) against control areas that did not. They found large and lasting effects in terms of improved housing quality.) Simply setting expectations for road structure — without coercing anyone to give up land by eminent domain — seems to be amazingly productive for newly developing cities, and possibly a vey cost-effective development intervention in the context of LMICs.

IV

Beauty in a building, like pollution, is an externality. But it is a positive externality: passers-by enjoy it freely, lifting the desirability of an area (or not, as the case may be). The developer doesn’t capture that value, so they are under-incentivised to build beautiful (or humane, delightful, evocative, iconic, friendly) structures. In other words: unlike interior design, we are all subjected to architecture.

In cities with very rich architectural traditions, I think the ‘conservation’ argument against planning liberalisation has some force. That is, that the gain of a twice-as-dense apartment block might be overcounted versus the loss of the (sidenote: Like the Haussmannians in Paris or Alamo Park’s Panted Ladies.). Some of the loss could be measured through declines in nearby land value, but surely not all.

For most, for now, beauty is very secondary to the necessities of living in a city: rent, mobility, proximity to jobs. But I mention this because I still wonder what Bertaud has to say about aesthetic value, and the in-practice architecturally soulless character of many market-directed new builds.

If (say) high-income cities in Europe and the US do begin to liberalise planning restriction, and the ‘hard costs’ of construction finally decline, then we might think seriously about smart ways to incentivise and subsidise beauty (I wish I had a better word than that). Indeed if the buildings waiting on the other side of planning liberalisation were very attractive, then a voting public might look more favourably on easing restrictions on building them. I like Samuel Hughes’ ideas of “gentle density” and “easy style” for this reason.

As it is, my ebook reader shows (sidenote: both (weirdly enough) referencing the topography of a city).

Still, few if any truly attractive cities were designed, de novo, by grand plans. Paris is home to singular designs — the Place Vendôme, Place des Vosges, Champs-Élysées — but in a clumsy, incremental patchwork. L’Enfant designed the foundational layout for DC, but the city was built in tranches, over decades, by many architects. London’s Regent Street maintains its harmonious character because a single landowner — the Crown Estate — (sidenote: Samuel Hughes points out this difference in ownership structure explains the difference in appearance between Regent Street and Oxford Street. Arguably Oxford street sees a kind of ‘race to the bottom’ dynamic, where neighbouring shops clamour for your attention, because its private rental structure simply allocates facades to the highest bids.). But these examples don’t violate something like the central lesson of the book, which is that flourishing cities are cultivated, not designed. Municipal planners, like bloodletting medieval physicians, typically don’t succeed in healing what they misunderstand.

This is Gall’s law embodied: a complex system that works is always found to have evolved from a simple system that worked.

Back to writing