You don't need to read the news

Published 9 April 2023 ⋅ Comment on Substack

Back to writingContents (click to toggle)

2,238 words • 12 min read

I think that some people feel obliged to read the news, and that they don’t need to. Reading the news (for perhaps hours per week) might feel virtuous or necessary, but mostly I think it is neither.

To clarify, I’m talking about mainstream newspapers, magazines, and TV news channels. And I’m taking aim at the claim that regularly reading or watching news is positively important (aside from being entertaining).

I’ll give three reasons:

- The news suggests many things are getting worse than they are

- The news suggests an incomplete picture of the world’s problems

- You don’t need to read the news to be good at predicting important outcomes

I

The first reason is that the news can misleadingly suggest that trends are pointing in a far more reliably pessimistic direction than they are, even absent factual errors. This happens through judgements about what counts as newsworthy.

This 2023 study (PDF) looked at a bunch of fairly high-powered RCTs (n ≈ 22k) run by the news site Upworthy, to figure out the causal effect of negative words on how likely people are to click through and read the article. The headline finding was that — stop press — negativity drives online news consumption. Concretely, each additional negative word in a typical headline increased the click-through rate by just over 2%. A reasonable inference is that where the headlines lead, the content follows.

A hot new study with a depressing conclusion? I cannot help but read this!

But if news stories skew negative, does that bias beliefs? Consider: in all but two years since 1972, the majority of survey-takers in an annual Gallup poll claimed that they believed crime had increased in the U.S. since the previous year. Measuring rates of crime is complicated, but the big picture in fact appears to be that rates mostly decreased over this period. Presumably, the explanation must involve the fact that news media will report on particular incidents of violent crime, and on any indications that various kinds of crime are on the rise (even temporarily). But they are less likely to report on indications that levels of crime are declining (in some sense this is just an absence of news). The survey respondents consistently perceived slightly less decline in local rates of crime — presumably they just had more evidence in front of their eyes to discharge the impression from (sidenote: Maybe there is a similar dynamic at play when people guess that others are less happy than they report to be, in every country which has been surveyed.)

I think this generalises: one reason negative headlines get more attention may be that destruction tends to happen more suddenly and unexpectedly than improvement, which makes for better news. Like a descending Shepard tone, the news can conjure illusions of pessimistic trends when none exist.

II

Newsworthiness (in practice) is not evenly distributed according to importance. From the point of view of humanity, some very big stories get passed over, and some relatively smaller stories get (sidenote: I’m not claiming that newsworthiness is totally uncorrelated with importance; just that important topics get missed and others get overblown.).

Sometimes, stories get picked up through plain luck, and then news begets news: what’s newsworthy becomes newsworthy (causally) because there was news written about it.

Other times, the reason is parochialism: some stories are big in absolute terms, but they’re just about things which are mostly very far away. Think: progress against malaria and other tropical diseases. And this bit from Adam Smith’s Theory of Moral Sentiments.

↑ ‘View of the World from 9th Avenue’

Related is the bias towards the identifiable (over the merely statistical) victim. When baby Jessica McClure fell into a well in her aunt’s backyard, her unfolding (and eventually successful) rescue became a nationwide news story, generating donations even after the rescue effort had no use for more donations; enough to eventually fill a million-dollar trust fund.

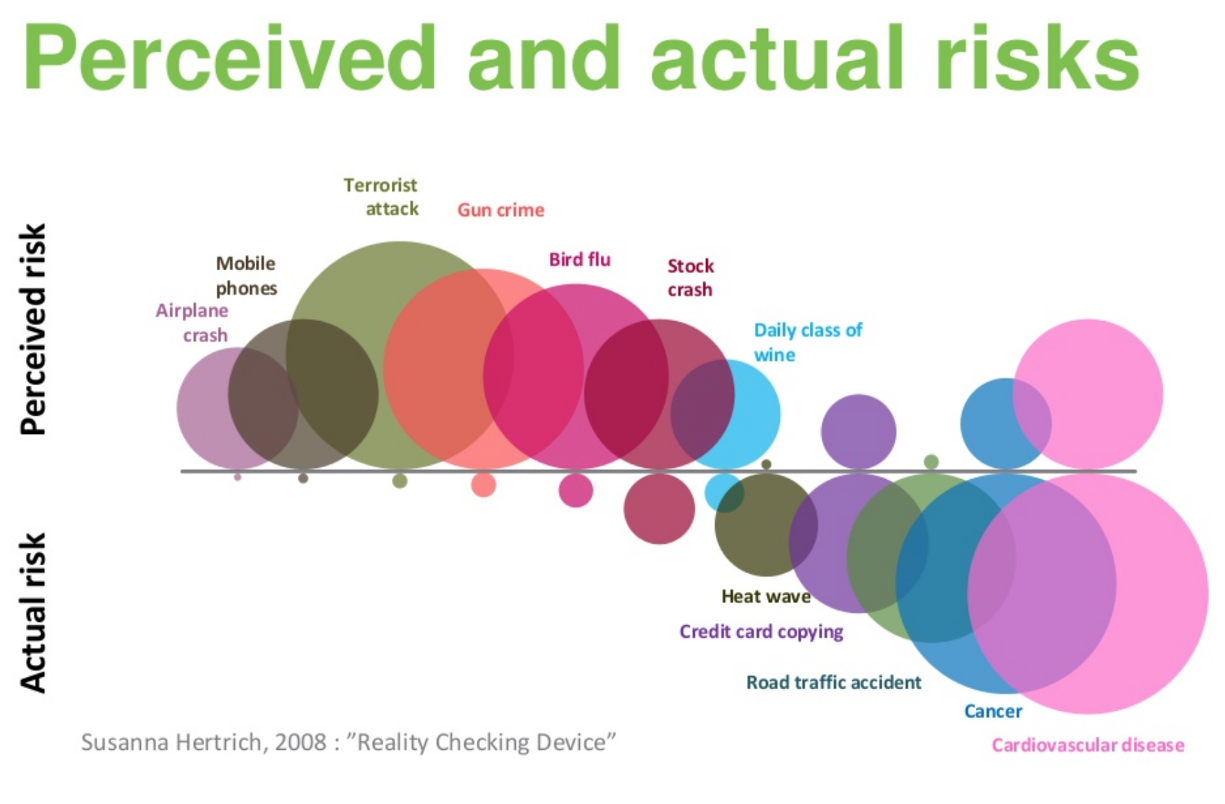

Or consider how much more ink is spilled per life affected by stories which play to fear, especially of the alien or malicious. Stories about threats or incidents of domestic terror, plane crashes, or nuclear meltdowns are viscerally attention-grabbing; stories about (sidenote: The researcher Peter Sandman has this slogan “Risk = Hazard + Outrage”. He finds that risks tend to feel more outrageous, and ∴ be overweighted, when they’re more unfamiliar, uncontrollable, unfair, acute virus continuous in time, delayed in time from the cause, produce identifiable victims, caused by immoral activities, or generated by human decisions versus ‘acts of God’. The graphic below is by Susanna Hertrich, drawing on this research.). One response is because the former class of ‘disasters’ are avoidable, while the more frequent and in absolute terms bigger killers are unavoidable. But I’d just encourage you to really consider whether that’s true.

All these examples are different manifestations of scope neglect, and I’m arguing that the news doesn’t spend ink in proportion to an issue’s true scope, and so probably reinforces scope neglect.

On the other hand, some stories don’t involve any clear cast of characters with clearly identifiable motives; or they’re difficult to pithily summarise; or they might look more like trends than narratives.

For example: AI looks like it will plausibly become the most transformative technological advance this century, perhaps ever. There is no shortage of good pieces about advances like ChatGPT or Bing’s chatbot. But interviews with top ML researchers remain curiously rare. One reason might be that the the most important technical stories and trends don’t really fit familiar narratives or feature familiar characters (even though these stories are extremely important and not boring).

I’m not trying to make a point about political bias: sampling news from the other side of the political aisle will give you alternative opinions on roughly the same topics. Instead I’m saying that if you want to understand important things in the world, the news is likely to suggest an incomplete list of topics. Notice also that this claim is compatible with the news being factually accurate all of the time.

I’m not arguing this is a conspiracy on the part of the news, to keep stories simple and familiar. Rather the news responds to demand, and I’ll keep coming back for the simple and familiar stories. But the things I’d probably most benefit from learning are nuanced and unfamiliar. So as long as I want to learn about the world efficiently, I’d do well by looking past the news. I think this also words at the group level: as long as most people are guided by the news, then you contribute an important kind of diversity in thinking about what’s important in the world — a fix for the (sidenote: I’m almost certain I saw this phrase in a Joan Didion book, but I can’t find it when I search for it.).

III

The news just doesn’t seem to be necessary to make accurate and well-calibrated forecasts of important events.

Consider the platform Metaculus, where anyone can sign up to make predictions on a huge range of forecasting questions, and gradually build up a public track record. I was listening to a podcast interview with (at the time) the top-rated forecaster on Metaculus called Datscilly. 18 months after taking up forecasting, he won nearly $50,000 in the IARPA Geopolitical Forecasting Challenge where he placed second.

Datscilly doesn’t read the news: “I don’t read the news […] I don’t’ have geopolitics knowledge”. When he’s investigating a question like this one, he’ll go to the sources that news outlets might use to piece together their reports, but he doesn’t need to see how a reporter editorialised the sources.

There is a field of study around forecasting that asks: what makes people accurate? Which kinds of people are unusually prescient about world events, and who is unusually overconfident? Philip Tetlock effectively inaugurated the field with a major experiment conducted with U.S. intelligence agencies. He chose two hundred and eighty-four people, including many who made their living “commenting or offering advice on political and economic trends”. Then he began asking them to make predictions. By the end of the study, he had collected and analysed some 82,361 different multiple-choice predictions. One result stood out: those participants who represented the commentariat — the kind of talking head that makes it into editorial pages and studio interviews and is called a pundit — would have lost to dart throwing chimps.

In more words: most of the questions had three answers, and the pundits chose the right answer less than a third of the time. In fact, Tetlock found that inaccuracy increased with eminence: fame selects for overconfidence.

I conclude: as long as understanding the world has a lot to do with being able to predict it, the news isn’t important.

We can say these things because it’s possible to test for accuracy on testable predictions. But we might expect the lesson to extend to less testable views — like views about what should be done, what people should be talking about, or just vague senses of foreboding. Take your pick of such a view, and it’s often possible to marshal exclusively true facts to support it. Since news pundits of the opinion column variety don’t typically impress in the arena of testable predictions, we might treat their opinions as more generally unreliable — despite their credentials as “person in the news media”. Precisely true facts don’t tightly constrain broad conclusions.

Here is Oliver Habryka in a recent interview:

Ultimately, most of the world, when they say things, are playing a dance that has usually as its primary objective, like, increasing the reputation of themselves, or the reputation of their allies […] while of course not saying technically false things. But not saying technically false things really is a very small impediment to your ability to tell stories that support arbitrary conclusions.

IV

Here’s a fair response to all this: ditching the news means abdicating your responsibility to maintain at least a rough understanding of the political systems you are part of; it’s a luxury to just check out of those conversations. I see the spirit, but I’d guess that there are more enlightening ways of understanding politics. For example, I read about US politics and politicians, enough to trick myself into thinking I more or less grasped how US laws are actually made. But I totally didn’t. I was familiar with the words, but not the processes they referred to, not really.

That points to some constructive advice which I’ve found useful: to seek explanations before news or opinions which assumes knowledge of them. Even if it feels embarrassingly late to be reading an explainer (I recently read this literal article).

Here’s another response: yes, the news gives a warped and incomplete picture of what’s important in the world. But it does a very effective job of packaging many things which are important and summarising them for me. So I am being deprived of something in not watching the news. And alternatives to the news (like nonfiction books) typically take more time and attention to digest, which is a luxury you can’t assume everyone has.

I think this is reasonable. But the main feeling I wanted to convey was less about exhorting people to expand their reading beyond the news, and was more about just relieving the sense of obligation to read the news. The news can be entertaining, but it is also very often entirely depressing. I think it is important to be informed about the world, in the sense of getting the big picture broadly right. But that doesn’t mean subjecting yourself to fresh reminders of small catastrophes as they unfold, and it could be an act of kindness to yourself to just drop the game of keeping up with them.

You could also read Bryan Caplan post: ‘Mainstream Media is Worse Than Silence’. It’s more strongly worded than mine.

Back to writing