Intro to Longtermism

Published 26 January 2021

Back to writingContents (click to toggle)

9,564 words • 48 min read

‘Longtermism’ refers to a set of ethical views concerned about protecting and improving the long-run future. Although concern for the long-run future is not a new idea, only recently has a serious intellectual project emerged around it — asking whether it is legitimate, and what it implies.

Can we plausibly influence the very long-run future? If so, how important could it be that we do what we can to improve its prospects? To these questions, an increasing number of apparently sensible people are answering: “yes we can, and very”. If we discover that there are things we can do to improve how things turn out very far into the future, that doing so is extremely important, and that we’re not currently taking those opportunities — then longtermism would turn out to matter a great deal.

You might also want to learn more about longtermism because it could end up influencing decision-making, whether or not it’s true or important. If you’re into effective altruism, you might want to know why a significant amount of EA-influenced philanthropic spending is focusing on longtermist (especially risk-focused) interventions; especially when urgent and pressing problems like extreme poverty and factory farming remain tractable, neglected, and important.

The plan for this post, then, is to explain what longtermism is, why it could be important, and what some possible objections look like.

By ‘longtermism’, I have in mind a serious ethical concern with protecting and improving the long-run future. By ‘the long-run future’, I means something like ‘the period from now to many thousands of years in the future, or much further’ — not just this century. I’ll also associate longtermism with a couple specific claims: first, that this moment in history could be a time of extraordinary influence over the long-run future; and second, that society currently falls far short of what it could be doing to ensure the long-run future goes well. I mention some more precise definitions nearer the end.

The case for longtermism

The most popular argument for longtermism in the (tiny) extant philosophical literature is consequentialist in flavour, meaning it appeals to the importance and size of the effects certain actions can have on the world as reasons for taking those actions. The argument has roughly three parts. First, there is an observation that the goodness or badness of some outcome doesn’t depend on when it happens. Second, there’s an empirical claim that the future could plausibly be very big (in duration and number of lives), and very valuable (full of worthwhile lives and other good things). Third, there’s another empirical claim that there are things we can do today with a decent shot of influencing that future by a not-ridiculously-small amount, and with a not-ridiculously-small chance. Putting these together, the conclusion is that there are things we can do today with a decent shot at making an enormously valuable difference.

Let’s go through these stages.

Future effects matter just as much

Longtermists claim that, all else equal, (far) future effects matter intrinsically just as much as more immediate effects.

Note that this claim isn’t denying that there are many practical reasons to prefer making things go well right now versus trying to make things go well 1,000 years from now. The most obvious is that it’s typically far easier to reliably affect how things go in the immediate future. Conversely, it’s normally very unclear how to reliably affect what happens in the far future. After all, we know about today’s pressing problems, but not what pressing problems the world might face a few centuries from now.

Another reason is that benefits often compound, meaning the best way to improve the (far) future is often to improve things right now. Consider money. Immediate benefits are often instrumentally useful for future benefits. Suppose I have some medicine which treats a tropical disease. Should I distribute it now, or should I use it a few decades or centuries from now? Using the medicine now would not only help improve people’s lives now, it might also help the region in which you use it develop, making those people less likely to need help in the future.

Longtermism isn’t denying any of that, because of the ‘all else equal’ part. The idea is more like: suppose you can confer some fixed total amount of harms or benefits right now, or many years. We’re imagining no knock-on effects, and you’re equally confident you can confer these harms or benefits at either time. Is there something about conferring those harms or benefits in the (far) future which makes them intrinsically less (dis)valuable? In other words, might we be prepared to sacrifice less to avoid the same amount of harm if we were confident it would occur in the (far) future, rather than next year? Longtermism answers ‘no’. There is no principled reason, it claims, for intrinsically valuing (far) future effects any less than more immediate effects.

Why think this? On reflection, the fact that something happens far away from us in space doesn’t make it less intrinsically bad than if it happened nearer to us. And people who live on the other side of the world aren’t somehow worth less just because they’re far away from us. This realisation is part of a family of views called cosmopolitanism. Longtermism simply draws an analogy from space to time. If there’s no good reason to think that things matter less as they become more spatially distant, why think things matter less if they occur further out in time? In this way, longtermists suggest, we should embrace (sidenote: It may be useful to think of the universe as a ‘block’, extruded along a temporal dimension.)

There are two broad objections to the claim that the value of an outcome is the same no matter when it occurs. One reason is that we might want to ‘discount’ the intrinsic value of future welfare, and other things that matter. In fact, governments do employ such a ‘social discount rate’ when they do cost-benefit analyses. Another kind of reason appeals to the fact that outcomes in the future affect people who don’t exist today. I’ll tackle the first objection now and the second (thornier) one in the ‘objections’ section.

Discounting

The simplest version of a social discount rate scales down the value of costs and benefits by a fixed proportion every successive year. Very few moral philosophers have defended such crude discount rates.[1]

In fact, the reason governments employ a social discount rate is largely a matter of electoral politics than deep ethical reflection. On the whole, voters prefer to see slightly smaller benefits soon compared to slightly larger benefits a long time from now. Plausibly, this gives governments a democratic reason to employ a social discount rate. But the question of whether governments should respond to this public opinion is separate from the question of whether that opinion is right.

Also, economic analyses sometimes yield surprising conclusions when a social discount rate isn’t concluded. This can be taken as a reason for including such a discount rate, and thinking it’s sensible to use one. But longtermists could suggest this gets things the wrong way around: since a social discount rate doesn’t make much independent sense, maybe we should take those surprising recommendations more seriously.

Here’s an argument against ‘pure time discounting’ from Parfit (1984). Suppose you bury some glass in a forest. In one case, a child steps on the glass in 10 years’ time, and hurts herself. In the other case, a child steps on the glass in 110 years’ time, and hurts herself just as much. If we discounted welfare by 5% every year, we would have to think that the second case is over 100 times less bad than the first — which it obviously isn’t. Since discounting is exponential, this shows that even a modest-seeming annual discount rate implies wildly implausible differences in intrinsic value over large enough timescales. Applying even a 3% discount rate implies that outcomes now are more than 2 million times more intrinsically valuable than outcomes 500 years from now.

Consider how a decision-maker from the past would have weighed our interests in applying such a discount rate. Does it sound right that a despotic ruler from the year 1500 could have justified some slow ecological disaster on the grounds that (sidenote: One pedantic, but optimistic, point is that while humans do tend to discount future goods, they don’t tend to discount them exponentially. Instead, people tend to discount hyperbolically — where the discount rate they apply is inconsistent over time. Over short time horizons, we discount steeply. Over long time horizons, we discount less steeply. For instance, many people would prefer £20 now to £30 one month from now, but few people would prefer £20 one year from now to £30 a year and a month from now. I say this is an optimistic point because it means that most people think (or at least behave as if) some constant discount rate is less and less reasonable the further out it is projected. In other words, people are more inclined to care about the very long-run future relative to the not-so-long-run future than constant discount rates imply.)?

The long-run future could be enormously valuable

By ‘future’, we mean ‘our future’ — our descendants and the lives they lead. You could use the phrase ‘humanity’s future’, but note that ‘humanity’ we mean our descendants: not necessarily just the species Homo sapiens. We’re interested in how big and valuable the future could be, and then we’ll ask whether we might have some say over that value. Neither of those things depends on the biological species of our descendants.

How big and valuable could our future be? To begin with, a typical mammalian species survives for an average 500,000 years. Since Homo sapiens have been around for around 300,000 years, then we might expect to have about 200,000 years left. This is not an upper bound: one way in which Homo sapiens is not a typical mammalian species could be that we are able to anticipate and (sidenote: Note also that humans make up about 100 times the biomass of any large wild animal that has ever lived.)

It might also be instructive to look to the future of the Earth. Assuming we don’t somehow change things, it looks like our planet will remain habitable for about another billion years (before it gets sterilised by the sun). If humanity survived for just 1% of that time, and similar numbers of people lived per-century as in the recent past, then we should expect at least a quadrillion future human lives.

Since we’re interested in the size of the future, it’s important to consider that humanity could choose to spread far beyond Earth. We could settle other planets, or even construct vast life-sustaining structures, and early investigations suggest this really could be practically feasible.

If humanity does spread beyond Earth, it could spread unimaginably far and wide, choosing from a wide range of extraordinary futures. The number of stars in the affectable universe, and the number of years over which we may be able to harness their energy, are literally astronomical. And since we would become dispersed over huge stretches of space, we would become less vulnerable to certain one-shot ‘existential catastrophes’.

You shouldn’t take these precise numbers too seriously, and it’s right to be a bit suspicious of crudely extrapolating from past trends like ‘humans per century’. What matters is multiple signs point towards the enormous potential — even likely — size of humanity’s future.

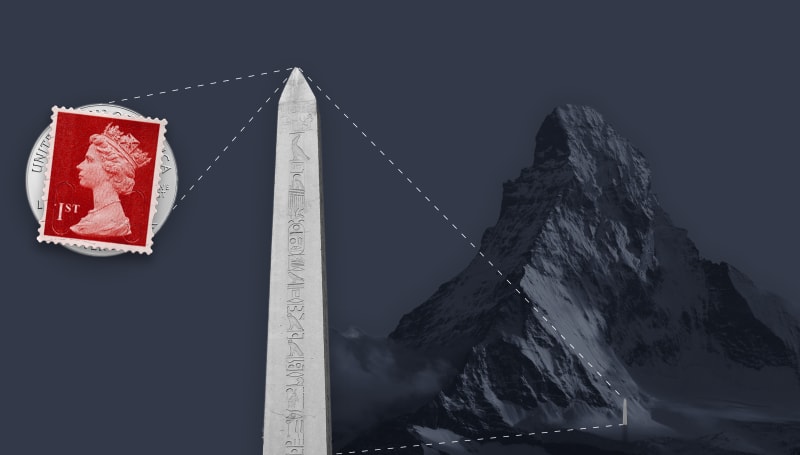

Metaphors do the same thing in a more creative way. For instance, Greaves and MacAskill analogise humanity’s story to a book-length tale, and note that we may well be on the very first page. This makes sense — about 100 billion humans have ever been born on Earth, and we’ve just seen that at least a thousand times as many might yet be born. Here’s another from Roman Krznaric’s book The Good Ancestor: if the distance from your face to your outstretched hand represents the age of the earth, one stroke of a nail file would erase human history. However, my favourite metaphor comes from physicist James Jeans. Imagine a postage stamp on a single coin. If the thickness of the coin and stamp combined represents our lifetime as a species, then the thickness of the stamp alone represents the extent of recorded human civilisation. Now imagine placing the coin on top of a 20-metre tall obelisk. If the stamp represents the entire sweep of human civilisation, the obelisk represents the age of the Earth. Now we can consider the future. A 5-metre tall tree on the postage stamp represents the Earth’s habitable future. And behind this arrangement, the height of the Matterhorn mountain represents the habitable future of the universe.

If all goes well, the future could also be full of things that matter — overwhelmingly more good than bad. To begin with, technological progress could continue to eliminate material scarcity and improve living conditions. We have already made staggering progress: the fraction of people living in extreme poverty fell from around 90% in 1820 to less than 10% in 2015. Over the same period, child mortality fell from over 40% to less than 5%, and the number of people living in a democracy increased from less than 1%, to most people in the world. Arguably it would be better to have been born into a middle-class American family in the 1980s than to be born as the king of France around the year 1700. Yet, looking forward, we might expect opportunities and capabilities available to a person born in the further future which a present-day billionaire can only dream of.

Beyond quality of life, you might also care intrinsically about art and beauty, the reach of justice, or the pursuit of truth and knowledge for their own sakes. Along with material abundance and more basic human development, all of these things could flourish and multiply beyond levels they have ever reached before.

Again — longtermism is not claiming to know what humanity’s future, or even its most likely future, will be. What matters is that the future could potentially be enormously large, and full of things that matter.

We can do things to significantly and reliably affect that future

What makes the enormous potential of our future morally significant is the possibility that we might be able to influence it.

This isn’t at all obvious: most people from history were not really in a position to shape the long-run future. Yet, there’s a compelling case for thinking that this moment in history could be a point of extraordinary influence.

First, I’ll briefly consider the kind of ‘influence’ that would end up being morally significant.

There is a trivial sense in which almost anything we do affects the far future, of course. Things we do now cause future events. Those events become causes of further events, and so on. And small causes sometimes amount to tipping points for effects much larger in scale than the immediate or intended effect of your initial action. As such, the effects of your decisions today ripple forward unpredictably and chaotically. The far future is just the result of all those ripples we send into the future.

The mere fact that our actions affect the far future is poetic but not itself important. What would matter is if we can do so reliably, and in ways that matter (morally).

Suppose you’re deciding whether to help an old lady across the road. The short-term effects are clear enough, and they’re best when you help the old lady. What about longer-run effects? Well, choosing to help the old lady could hold up traffic and lead to a future dictator being conceived later this evening. The reason this consideration doesn’t weigh against helping the old lady is that symmetrical considerations cut the other way — not helping the old lady could just as easily play a role in precipitating some future catastrophe. Since you don’t have any reason to believe either outcome is more likely for either option, these worries ‘cancel’ or ‘wash out’. So you’re not reliably influencing the likelihood of future dictators by helping the old lady.

On the other hand, there are some things we can do which can reliably influence the future, but only by influencing it in ways that are (morally) unimportant. Such actions trade off reliability at the cost of insignificance. You could carve your initials in a strong stone, or bury a time capsule. In the first case, your stone might be spotted by many people, but none of these people are likely to care much. In the second case, your time capsule might be discovered far in the future, but its discovery would amount to a single event isolated in time, rather than persisting over it.

What would matter enormously is if we could identify some actions we could take now which could (i) reliably influence how the future plays out over the long run in (ii) significant, nontrivial ways. One class of actions might involve effects which persist, or even compound, across time. Another class might help tip the balance from a much worse to a much better ‘attractor’ state — some civilisational outcome which is easy to fall into and potentially very difficult to leave.

The strongest example of an ‘attractor’ state is an ‘existential catastrophe’ — a permanent curtailment of humanity’s potential. The most salient kind of existential catastrophe is extinction. Despite what I said earlier about the possibility of surviving a long time as a species, we also know that human extinction is possible. One obvious reason is that we can witness the rapid extinction of other animal species in real-time, and often humans are responsible for those extinctions.

Human extinction might have a natural cause, like (sidenote: I recently wrote about risks from asteroids here.). It might also be caused by human inventions — through an engineered pandemic, unaligned artificial intelligence, or even some mostly unforeseen technology.

Other than extinction, we could also end up ‘locked-in’ to a bad and close to inescapable political regime, facilitated by widespread surveillance.

Might there be anything we can do to reliably decrease the likelihood of some of these existential catastrophes? It doesn’t seem ridiculous to think there is.

We might, for instance, build an asteroid defence system, investigate ways to make advanced artificial intelligence safer through governance or technical methods, strengthen the infrastructure that regulates experimentation on dangerous artificial human pathogens, or make existing political regimes more robust to totalitarian takeover. Few of us are in a place to do that work directly right now, but many of us are in a position to encourage such initiatives with our support, or even to shift our career toward working on such causes.

What about changes which improve the future more incrementally? Some surprising econometric evidence suggests that differences in cultural attitudes sometimes persist for centuries. For instance, the anthropologist Joseph Henrich suggests that the spread of the Protestant church explained why the industrial revolution occurred in Europe, in turn explaining much of Europe’s subsequent cultural and economic success. You might also identify some moments from history where which values a political regime or culture decided on were very sensitive to discussions between a few people in a narrow window of time, but where those values ended up influencing enormous stretches of history, for better or worse. For instance, the belief system of Confucianism has determined much of Chinese history, but it’s one of a few belief systems (including Legalism and Daoism) which could have taken precedent before the reigning emperor during the Han dynasty was persuaded to embrace Confucianism, after which point it became something like the official ideology of the state for an almost continuous two millenia.

Of course, it is one thing to notice these causal differences ex post, and another thing to guess what changes now could have similar effects in the far future. But it’s significant that long stretches of history have been determined by some fairly contingent decisions about values and institutions. In other words, history is not entirely dictated by unstoppable trends beyond the control of particular people or groups.

Some people have suggested that this century could be a time of unusual influence over the long-run future — a time where some contingent decisions could get made which might persist for a very long time. The main argument for this is that we appear to be living during a period of unprecedented and unsustainably rapid technological change. For this reason, Holden Karnofsky argues that we could be living in the most important century ever.

Putting it together

Plausibly, there are some things we can do to reliably and significantly influence how the future turns out over long timescales. Granting this, what makes these things so valuable or important? On this argument, the answer is straightforward: the future is such a vast repository of potential value, that anything we can do now to improve or protect it by even a modest fraction could end up being proportionally valuable. In other words, the stakes look astonishingly high.

That said, in other instances you don’t need philosophical arguments about the size of the future to realise we should really do something about e.g. potentially catastrophic risks from nuclear weapons, engineered pandemics, or powerful and unaligned AI. On those fronts, the cumulative risk between now and even when our own grandchildren grow up looks unacceptably high; and it looks like we can do more than just making modest changes to the level of risk. Often it does just look like the world has gone insane.

In both the case of mitigating risks, and influencing which values potentially get ‘locked-in’ over very long periods of time, actions which reliably and lastingly influence the future derive their importance from how much value the future might contain, and also from the fact that the extent and quality of our future could depends on things we do now.

You might consider an analogy to the prudential case — swapping out the entire future for your future, and only considering what would make your life go best. Suppose that one day you learned that your ageing process had stopped. Maybe scientists identified the gene for ageing, and found that your ageing gene was missing. This amounts to learning that you now have much more control over how long you live than previously, because there’s no longer a process imposed on you from outside that puts a guaranteed ceiling on your lifespan. If you die in the next few centuries, it’ll most likely be due to an avoidable, and likely self-imposed, accident. What should you do?

To begin with, you might try a bit harder to avoid those avoidable risks to your life. If previously you had adopted an nonchalant attitude to wearing seatbelts and helmets, you probably want some new habits. You might also begin to spend more time and resources on things which compound their benefits over the long-run. If keeping up your smoking habit is likely to lead to lingering lung problems which are very hard or costly to cure, you might care much more about kicking that habit soon. And you might begin to care more about ‘meta’ skills, which require some work now but pay off over the rest of your life, like learning how to learn. You might want to set up checks against any slide into madness, boredom, destructive behaviour, or joining a cult — all of which which living so long could make more likely. Once you’re confident it’s much less likely you’ll be killed or permanently disabled by a stupid accident any time soon, you might set aside a long period of time to reflect on how you actually want to spend your indefinitely long life. What should your guiding values be? You have some guesses, but you know your values have changed in the past, and it wouldn’t have made sense to set your entire life according to the values of your 12-year-old self. After all, there are so many things you could achieve in your life which your childhood self couldn’t even imagine — so maybe the best plans for your life are ones you haven’t yet conceived of. So, on hearing that you don’t have the ageing gene, you put those safety measures in place, and begin your period of reflection.

When you learned that your future could contain far more value than you originally thought, certain behaviours and actions became far more important than before. Yet, most of those behaviours were sensible things to do anyway. Far from diminishing their importance, this fact should only underline them.

Lastly, note that you don’t need to believe that the future is likely to be overwhelmingly good, or good at all, to care about actions that improve its trajectory. If anything, you might think that it’s more important to reach out a helping hand to future people living difficult lives, than to improve the lives of future people who are already well-off. If you noticed that you were personally on a trajectory towards e.g. ruinous addiction, the appropriate thing to do would be to try steering away from that trajectory to the best of your ability; likely not to give up or even choose to end your life.

For instance, some people think that unchecked climate change could eventually make life worse for most people than it is today. Recognising the size of that diminished future only provides an additional reason to care about doing something now to make climate change less bad.

Finally, note that longtermism is normally understood as a claim about what kind of actions happen to be incredibly good or important at the current margin. One thing that makes these actions look like they stand to do so much good is the fact that so little thought and effort has so far been directed towards improving and safeguarding the lives of future people in sensible, effective ways.

Suppose every member or your tribe will go terribly thirsty without water tonight, but one trip to the river to get water will be enough for everyone. Getting water should be a priority for your tribe, but only while nobody has bothered to get it. It doesn’t need to be a priority in the sense that everyone should make it a priority to go off and get water. And once somebody brings water, it wouldn’t make sense to keep prioritising it. Similarly, longtermism is rarely understood as an absolute claim to the effect that things would go best if all or even most people started worrying about improving humanity’s long-run future.

Neglectedness

It’s not enough that longtermist problems be important and solvable — because skilled people might already be queuing up to solve them. The longtermist claim that there are still big opportunities for positively influencing the long-run future therefore suggests that we’ve not yet filled those opportunities. In fact, this may be an understatement — there are reasons for thinking these actions are outstandingly neglected. This makes those actions seem even more worthwhile, since the most important opportunities for working on a problem are typically filled first, followed by slightly less important opportunities, and so on.

For instance, the philosopher Toby Ord estimates that bioweapons, including engineered pandemics, pose about 10 times more existential risk than the combined risk from nuclear war, runaway climate change, asteroids, supervolcanoes, and naturally arising pandemics. The Biological Weapons Convention is the international body responsible for the continued prohibition of these bioweapons — and its annual budget is less than that of the average MacDonald’s.

If actions aimed at improving or safeguarding the long-run future are so important, why expect them to be so neglected? The main reason is that future people don’t have a voice, because they don’t presently exist. It isn’t possible to cry out so loudly that your voice reaches back into the past. Obviously enfranchisement makes a difference for how decisions about the enfranchised group get made. When women were gradually enfranchised across most of the world, policies and laws were enacted that made women better off.

But women fought for their vote in the first place by making themselves heard, through protest and writing. Yet future people, because they don’t exist yet, are strictly unable to participate in politics. They are ‘voiceless’, but they still deserve moral status. They can still be seriously harmed or helped by political decisions.

Think about Peter Singer’s picture of the ‘expanding moral circle’. In part, it’s an empirical observation about the past, and in part it’s a guiding principle for the future. On this picture, human society has come to recognise the interests of progressively widening circles. Here’s the oversimplified version: at first, even the thought of helping a rival tribe was off the radar. With the arrival of the nation state, sympathies extended to conationals, even beyond one’s ethnic group. Nowadays, large numbers of people now restrict their diets to avoid harming nonhuman animals. We’ve come far: refusing to hunt animals out of concern for their feelings would have baffled hunter-gatherers whose moral circle extended as far as their small band. Yet, expanding the circle to include today’s nonhuman animals doesn’t mark the last possible stage, if none of these concentric circles contain people, animals, and other beings living in the (long-run) future.

Another, related, explanation for the neglectedness of future people has to do with ‘externalities’. If all decision makers are more or less self-interested, they’re only going to be prepared to do things which give back more benefits than they cost to do. Think at the level of a country: for some spending, e.g. on schools and infrastructure, the benefits mostly remain in your country. For other projects, it’s harder to contain the benefits to your country. One example is spending on research, because the world gets to learn the results, and so other countries benefit from the efforts of your country’s scientists. Because the benefits are shared but the costs are confined to you, your share of the total benefit might not be enough to outweigh the costs to you, even if the total (‘social’) benefit far outweighs the (‘private’) cost to you. This is called a ‘positive externality’. So it might not be in the self-interest of a country to pay for such ‘global public goods’, even if the world benefits enormously from them.

The reverse can happen just as easily, where the costs are distributed but the benefits are confined. This is a ‘negative externality’. The best example is pollution: one country’s emissions impose burdens on the entire world, but that country only bears a small fraction of the total burden. If there’s nothing in place to stop us, it might be worth it from a self-interested perspective to pollute, even if the total costs far outweigh the total benefits.

The externalities from actions which stand to influence the long-run future not only extend to people living in other countries, but also to people living in the future who are not alive today. As such, the positive externalities from improvements to the very long-run are enormous, and so are the negative externalities from ratcheting up threats to the entire potential of humanity. Modelling governments as roughly self-interested decision makers looking after their presently existing citizens, it would therefore be no surprise if they neglected long-term actions, even if the total benefits of longtermist decisions stood to massively outweigh their total costs. Such actions are not just global public goods, they’re intergenerational global public goods.

Going Further

Other framings

Above, I tried describing a broadly consequentialist argument for longtermism. In short: the future holds a vast amount of potential, and there are (plausibly) things we can do now to improve or safeguard that future. Given its potential size, even small proportional changes to how well the future goes could amount to enormous total changes. Further, we should expect some of the best such opportunities to remain open, because improving the long-run future is a public good, and because future people are disenfranchised. Because of the enormous difference such actions can make, they would be very good things to do. Note that you don’t need to be a card-carrying consequentialist to buy that long-term oriented actions are very good things to do, as long as you care about consequences at all. And any non-insane ethical view should care about consequences to some degree.

That said, there are other ways of framing longtermism. One argument invokes obligations to tradition and the past. Our forebears made sacrifices in the service of projects they hoped would far outlive them — such as advancing science or opposing authoritarianism. Many things are only worth doing in light of a long future, during which people can enjoy what you achieved. No cathedrals would have been built if the religious sects which built them didn’t expect to be around long after they were completed. As such, to drop the ball now wouldn’t only eliminate all of the future’s potential — it would also betray those efforts from the past.[2]

Another framing invokes ‘intergenerational justice’. Just as you might think that it’s unjust that so many people live in extreme poverty when so many other people enjoy outrageous wealth, you might also think that it would be unfair or unjust that people living in the far future were much worse off than us, or unable to enjoy things we take for granted. Just as there’s something we can do to make extremely poor people better off at comparably insignificant cost to ourselves, there’s something we can do to improve the lives of future people. At least, there are things we can do now to preserve valuable resources for the future. The most obvious examples are environmental: protecting species, natural spaces, water quality, and the climate itself. Interestingly, this thought has been operationalised as the ‘intergenerational solidarity index’ — a measure of ‘how much different nations provide for the (sidenote: Pedantically, I should note that thinking both (i) that equality of welfare between present and future generations matters intrinsically, and (ii) that future people are very likely to be better off than us, might support expropriating from future people to make ourselves better off (e.g. using more non-renwable natural resources than if you didn’t care about intergenerational equality). This seems a little strange.)

Finally, from an astronomical perspective, life looks to be exceptionally rare. We may very well represent the only intelligent life in our galaxy, or even the observable universe. Perhaps this confers on us a kind of ‘cosmic significance’ — a special responsibility to keep the flame of consciousness alive beyond this precipitous period of adolescence for our species.

Other definitions and stronger versions

By ‘longtermism’, I had in mind the fairly simple idea that we may be able to positively influence the long-run future, and that aiming to achieve this is extremely good and important.

Some ‘isms’ are precise enough to come with a single, undisputed, definition. Others, like feminism or environmentalism, are broad enough to accommodate many (often partially conflicting) definitions. I think longtermism is more like environmentalism in this sense. But it might still be worth looking at some more precise definitions.

The philosopher Will MacAskill suggests the following —

Longtermism is the view that: (i) Those who live at future times matter just as much, morally, as those who live today; (ii) Society currently privileges those who live today above those who will live in the future; and (iii) We should take action to rectify that, and help ensure the long-run future goes well.

This means that longtermism would become false if society ever stopped privelaging present lives over future lives.

Other minimal definitions don’t depend on changeable facts about society. Hilary Greaves suggests something like —

The view that the (intrinsic) value of an outcome is the same no matter what time it occurs.

If that were true today, it would be true always.

Some versions of longtermism from the proper philosophical literature go further than the above, and make some claim about the high relative importance of influencing the long-run future over other kinds of morally relevant activities.

Nick Beckstead’s ‘On the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future’ marks the first serious discussion of longtermism in analytic philosophy. His thesis:

From a global perspective, (sidenote: An ‘expectation’ comes from adding up the products of outcomes and their respective (subjective) probabilities, in order to attribute a value to something whose outcome is uncertain. If I offer to give you £10 if a coin flip comes up heads and nothing otherwise, you stand to make £10 × 0.5 + £0 × 0.5 = £5 in expectation.) is that we do what is best (in expectation) for the general trajectory along which our descendants develop over the coming millions, billions, and trillions of years.

More recently, Hilary Greaves and Will MacAskill have made a tentative case for what they call ‘strong longtermism’.

Axiological strong longtermism: In the most important decision situations facing agents today, (i) Every option that is near-best overall is near-best for the far future; and (ii) Every option that is near-best overall delivers much larger benefits in the far future than in the near future.

Deontic strong longtermism: In the most important decision situations facing agents today, (i) One ought to choose an option that is near-best for the far future; and (ii) One ought to choose an option that delivers much larger benefits in the far future than in the near future.

Roughly speaking, ‘axiology’ has to do with what’s best to do, and ‘deontology’ has to do with what you should do. That’s why Greaves and MacAskill give two versions of strong longtermism — it could be the case that actions which stand to influence the very long-run future are best in terms of their expected outcomes, but not the case that we must always do them (you might think this is unreasonably demanding).

The idea being expressed is therefore something like the following: in cases such as figuring out what to do with your career, or where to spend money to make a positive difference, you’ll often have a lot of choices. Perhaps surprisingly, the best options are pretty much always among the (relatively few) options directed at making the long-run future go better. Indeed, the reason they are the best options overall is almost always because they stand to improve the far future by so much.

Please note that you do not have to agree with strong longtermism in order to believe in longtermism! Similarly, it’s perfectly fine to call yourself a feminist without buying into a single, precise, and strong statement of what feminism is supposed to be.

Objections

Some people find longtermism hard to get intuitively excited about. There are so many pressing problems in the world, and we have a lot of robust evidence about which solutions work for them. In many cases, those solutions also turn out to be remarkably cost-effective. Now some people are claiming that other actions may be just as good, if not better, because they stand to influence the very long-run future. By their nature, these activities are backed by less robust evidence, and primarily look after the interests of people who don’t yet exist.

The proponent of longtermism needs to tell a convincing story about why these uneasy intuitions are so widespread, if they’re indeed so misguided. They also need to respond to more particular objections.

Here’s one quick explanation of why we might sometimes feel uneasy about the case for longtermism. From an evolutionary perspective (both cultural and biological evolution), perhaps there’s virtually no opportunity for the emergence of a moral impulse to care about one’s ancestors long into the future — because such an impulse would lose out to shorter-term impulses before it’s able to get a footing in the gene pool or the set of values in a given culture. That’s not nearly enough to explain all uneasy intuitions about longtermism, of course.

What about particular objections to longtermism?

Person-affecting views

‘Person-affecting’ moral views try to capture the intuition that an act can only be good or bad if it is good or bad for someone (or some people). In particular, many people think that while it may be good to make somebody happier, it can’t be as good to literally make an extra (equivalently) happy person. Person-affecting views make sense of that intuition: making an extra happy person doesn’t benefit that person, because in the case where you didn’t make them, they don’t exist, so there’s no person who could have benefited from being created.

One upshot of person-affecting views is that failing to bring about the vast number of people which the future could contain isn’t the kind of tragedy which longtermism makes it up to be, because there’s nobody to complain of not having been created in the case where you don’t create them: nobody is made worse-off. Failing to bring about those lives would not be morally comparable to ending the lives of an equivalent number of actually existing people.

But person-affecting views have another, subtler, consequence. In comparing the longer-run effects of some options, you will be considering their effects on people who are not yet born. But it’s almost certain that the identities of these future people will be different between options. That’s because the identity of a person depends on their genetic material, which depends (among other things) on the result of a race between tens of millions of sperm cells. So basically anything you do today is likely to have ‘ripple effects’ which change the identities of nearly everyone on earth born after, say, 2050. Assuming the identity of nearly every future person is different between options, then it cannot be said of almost any future person that one option is better or worse than the other for that person. But because they claim that acts can only be good or bad if they are good or bad for particular people, person-affecting views therefore find it harder to explain why some acts are much better than others with respect to the longer-run future.

Perhaps this is a weakness of person-affecting views — or perhaps it reflects a real complication with claims about ‘improving’ the long-run future. To give an alternative to person-affecting views, the longtermist still needs to explain how some longterm futures are better than others, when the outcomes contain totally different people. And it’s not entirely straightforward to explain how one outcome can be better, if it’s better for nobody in particular!

Progress and self-contradiction

Some people interpret longtermism as implying that we should ignore pressing problems in favour of trying to foresee longer-term problems. In particular, they see longtermism as recommending that we try to slow down technological progress to allow our ‘wisdom’ to catch up, in order to minimise existential risk. However, these people point out, virtually all historical progress has been made by solving pressing problems, rather than trying to peer out beyond those problems into the further future. And many technological risks are mitigated not by slowing progress on their development, but by continuing progress: inventing new fixes. For instance, early aviation was expensive and accident-prone, and now it’s practically the safest mode of travel in the United States.

Similarly, longtermists sometimes join with ‘degrowth’ environmentalists in sounding the alarm about ‘unsustainable’ practices like resource extraction or pollution. But this too underestimates the capacity for human ingenuity to reliably outrun anticipated disasters. A paradigm example is Paul Ehrlich’s 1968 The Population Bomb, which predicted that “[i]n the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now”. Julian Simon, a business professor, made a wager with Ehrlich that “the cost of non-government-controlled raw materials (including grain and oil) will not rise in the long run.” Ehrlich chose five metals, and the bet was made in 1980 to be resolved in 1990. When 1990 came around, the price of every one of these metals had fallen. In this way, the modern world is a kind of growing patchwork of temporary solutions — but that’s the best and only way things could be.

By discouraging this kind of short-term problem solving, longtermism will slow down the kind of progress that matters. Further, by urging moderation and belt-tightening in the name of ‘sustainability’, longtermism is more likely to harm, rather than benefit, the longer-run future. In short, longtermism may be self-undermining.

This objection shares a structure with the following objection to utilitarianism: utilitarianism says that the best actions are those actions which maximise well-being. But if we only acted on that basis, without regard for values like truth-telling, autonomy, and rights — then people would become distrustful, anxious, and insignificant. Far from maximising well-being, this would likely make people worse off. Therefore, utilitarianism undermines itself.

Without assuming either longtermism or utilitarianism are true, it should be clear that this kind of ‘self-undermining’ argument doesn’t ultimately work. If the concrete actions utilitarianism seems to recommend fail to maximise well-being on reflection, then utilitarianism doesn’t actually recommend them. Analogously, if the actions apparently recommended by longtermism stand to make the long-run future worse, then longtermism doesn’t actually recommend them. At best, what these self-undermining arguments show is that the naive versions of the thesis, or naive extrapolations from them, need to be revised. But maybe that’s still an important point, and one worth taking seriously.

Risk aversion and recklessness

As explained, many efforts at improving the long-run future are highly uncertain, but they derive their ‘expected’ value from multiplying small probabilities with enormous payoffs. This is especially relevant for existential risks, where it may be good in expectation to move large amounts of money and resources towards mitigating those risks, even when it may be very unlikely they would transpire anyway. A natural response is to call this ‘reckless’: it seems like something’s gone wrong when what we ought to do is determined by outcomes with (sidenote: Modifying standard expected value theory to accommodate for these intuitions turns out to be very tricky. For instance, it’s hard to formalise any general rule that it may sometimes be permissible to ignore outcomes attached to small enough probabilities. Here’s a quick way to see this: in some sense, all or most the outcomes of your actions can be broken down into arbitrarily many outcomes with lower and lower individual probabilities. Applying such a rule may mean ignoring all or most the outcomes of your actions.).

Demandingness

Some critics point out that if we took strong versions of longtermism seriously, we would end up moraly obligated to make real sacrifices. For instance, we might forego some very large economic gains from risky technologies in order to build and implement ways of making them safer. Moreover, these sacrifices would have to be shared by everyone — including people who aren’t convinced by longtermism. On this line of cricitism, the sacrifices demanded of us by longtermism are unreasonably big; and it certainly can’t be right that everyone is forced to feel their effects.

To be sure, there are some difficult hypothetical questions about precisely how much a society should be prepared to sacrifice to ensure its own survival, or look after the interests of future members. But we are so far away from making those kinds of demanding sacrifices in the actual world that such questions look mostly irrelevant. As the philosopher Toby Ord points out, “we can state with confidence that humanity spends more on ice cream every year than on ensuring that the technologies we develop do not destroy us”. Meeting the ‘ice cream bar’ for spending wouldn’t be objectionably demanding at all, but we’re not even there yet.

Epistemic uncertainty: do we even know what to do?

If we were confident about the long-run effects of our actions, then probably we should care a great deal about those effects. However, in the real world, we’re often close to entirely clueless about the long-run effects of our actions. And we’re not only clueless in the ‘symmetric’ sense that I explained when considering whether you should help the old lady across the road. Sometimes, we’re clueless in a more ‘complex’ way: when there are reasons to expect our actions to have systematic effects on the long-run future, but it’s very hard to know whether those effects are likely to be good. Therefore, perhaps it’s so hard to predict long-run effects that the expected value of our options isn’t much determined by the long-run at all. Relatedly, perhaps it’s just far too difficult to find opportunities for reliably influencing the long-run future in a positive way.

Alexander Berger, co-CEO of Open Philanthropy, makes the point another way:

“When I think about the recommended interventions or practices for longtermists, I feel like they either quickly become pretty anodyne, or it’s quite hard to make the case that they are robustly good”.

One way of categorising longtermist interventions is to distinguish between ‘broad’ and ‘targeted’ approaches. Broad approaches focus on improving the world in ways that seem robustly good for the long-run future, such as reducing the likelihood of a conflict between great powers. Targeted approaches zoom in on more specific points of influence, such as by focusing on technical research to make sure the transition to transformative artificial intelligence goes well. On one hand, Berger is saying that you don’t especially need the entire longtermist worldview to see that ‘broad’ interventions are sensible things to do. On the other hand, the more targeted interventions often look like they’re focusing on fairly speculative scenarios — we need to be correct on a long list of philosophical and empirical guesses for such interventions to end up being important.

I think these are some the strongest worries about longtermism, but there are a few things to say. Because longtermism is a claim about what’s best to do on current margins, it only requires that we can identify some cases where the long-run effects of our actions are predictably good — there’s no assumption about how predictable long-run effects are in general. And it does seem hard to deny that some things we can do now can predictably influence the long-run future in fairly straightforward, positive ways. The best examples may be efforts to mitigate existential risk, such as boosting the tiny amount of funding the Biological Weapons Convention currently receives. Third, the longtermist could concede that we are currently very uncertain about how concretely to influence the long-run future, but this doesn’t mean giving up. Instead, it could mean turning our efforts towards becoming less uncertain, by doing empirical and theoretical research.

Totalitarianism

On the logic of longtermism, small sacrifices now can be justified by much larger anticipated benefits over the long-run future. Since the benefits could be very large, some people object that there could be no ceiling to the sacrifices that longtermism would recommend we make today. Further, this line of objection continues, longtermism says that the steep importance of safeguarding the long-term future suggests that certain freedoms might justifiably be curtailed in order to guide us through this especially risky period of the human story. But that sounds similar to historical justifications of totalitarianism. Since totalitarianism is very bad, this counts as a mark against longtermism.

The liberal philosopher Isaiah Berlin pithily summarises this kind of argument:

To make mankind just and happy and creative and harmonious forever - what could be too high a price to pay for that? To make such an omelette, there is surely no limit to the number of eggs that should be broken.

One response is to point out that the totalitarian regimes of the past failed so horrendously not because they believed in the general claim that sacrifices now may be worthwhile for a better future, but because they were wrong in a much more straightforward way — wrong that revolutionary violence and actual totalitarianism in practice make the world remotely better in the short or long term.

Another response is to note that a strong current of longtermism discusses how to reduce the likelihood of a great power conflict, improve institutional decision-making, and spread good (viz. liberal) political norms in general — in other words, how to secure an open society for our descendants.

But perhaps it would be too arrogant to entirely ignore the worry about longtermist ideas being used to justify political harms in the future, if its ideas end up getting twisted or misunderstood. We know that even very noble aspirations can eventually transform into terrible consequences in the hands of normal, fallible people. If that worry were legitimate, it would be very important to handle the idea of longtermism with care.

Conclusion

Arthur C. Clarke once wrote that “Two possibilities exist: either we are alone in the Universe or we are not. Both are equally terrifying”. Similarly, two broad possibilities exist for the long-run future: either humanity flourishes far into the future, or it does not. The second possibility is terrifying, and the first is so rarely discussed in normal conversation that it’s easy to forget it’s an option.

But both possibilities make clear the importance of safeguarding and improving humanity’s long-run future, because there are things we can do now to make the first possibility more likely.

Very important ethical ideas don’t come around often. Think of feminism, environmentalism, socialism, or neoliberalism. None emerge from a vacuum — they all grow from deep historical roots. Then fringe thinkers, working together or alone, systemise the idea. Books are published — A Vindication of the Rights of Women, Silent Spring, Capital, The Road To Serfdom. The ideas percolate through wider and wider circles, and reach a kind of critical mass. Then, for better or worse, the ideas get to affect change.

Plausibly, longtermism could be one of these ideas. If that’s true, then learning about it becomes especially important. I hope I’ve given a decent impression of what longtermism is, plus key motivations and objections.

Further Reading

- Against the Social Discount Rate — Tyler Cowen and Derek Parfit

- On the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future — Nick Beckstead

- The Case for Strong Longtermism — Will MacAskill and Hilary Greaves

- Reasons and Persons — Derek Parfit

- The Precipice — Toby Ord

- [Forthcoming] What We Owe the Future — Will MacAskill

- Future generations and their moral significance — 80,000 Hours

- ‘Longtermism’ (forum post) — Will MacAskill

- Orienting towards the long-term future — Joseph Carlsmith

- The Epistemic Challenge to Longtermism — Christian J. Tarsney

See Mogensen (2019), ‘The only ethical argument for positive 𝛿?’; Purves (2016), ‘The Case for Discounting the Future’; Mintz-Woo (2018), ‘A Philosopher’s Guide to Discounting’ ↩︎

See Kaczmarek & Beard (2020), ‘Human Extinction and Our Obligations to the Past’ ↩︎

Back to writing