A path from Seattle

Published 14 January 2024 ⋅ Comment on Substack

Back to writingContents (click to toggle)

1,499 words • 8 min read

Here’s a puzzle:

Imagine you begin a journey in Seattle WA, facing exactly due east. Then start traveling forward, in a straight line along the Earth’s surface.

You will travel across North America, and onto the Atlantic Ocean. Eventually, you will hit another country.

The question is: what is the first country you hit?

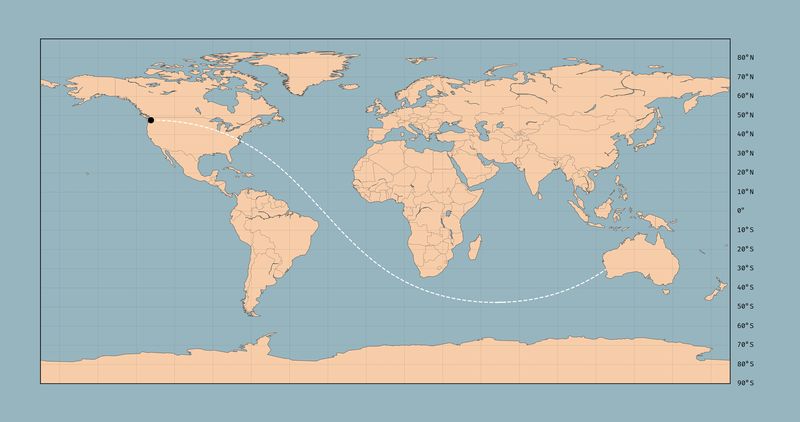

The image below shows your starting point, and the white arrow shows your starting direction (not path) immediately after leaving Seattle.

The rest of this post discusses the answer, so here’s your opportunity to make a guess of your own.

Full transparency: to some extent this is a ‘trick’ question. Make sure you’ve read the wording carefully, and see if you can understand the trick before revealing the answer.

Click me to reveal the answer

Australia. After pointing due east, and traveling continually forward in a straight line across the Earth’s surface, the next country you hit after you leave North America is Australia.

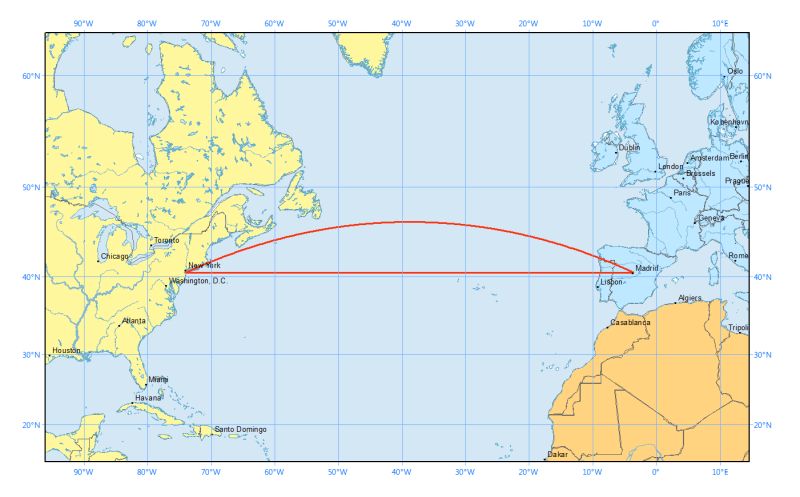

And here is the path you take (high res version)[1]:

Reaching the answer

Forget about the Earth for a second, and just imagine you’re standing on a big sphere.

Point in any direction, and begin walking forward along the surface of the sphere, without changing direction. This, I think, is the fairest interpretation of ‘straight line’.

Of course, you’ll loop round and return to where you started.

Notice also, just intuitively, how you’ll have walked the full circumference of the sphere: a ‘great circle’.

In order to trace out a smaller circle than that, you’d need to be constantly veering left or right.

In the original puzzle, you might have been imagining traveling a line of constant latitude — that is, always heading east.

But that is not a great circle, and so not a straight line: you’d need to be constantly turning left to maintain that path. Travelling laterally means changing direction with respect to the Earth’s surface.

To give an extreme example: imagine driving in a 10 meter radius around the North Pole. In order to always be traveling east — maintaining the same latitude — you’d need to be steering left the whole time.

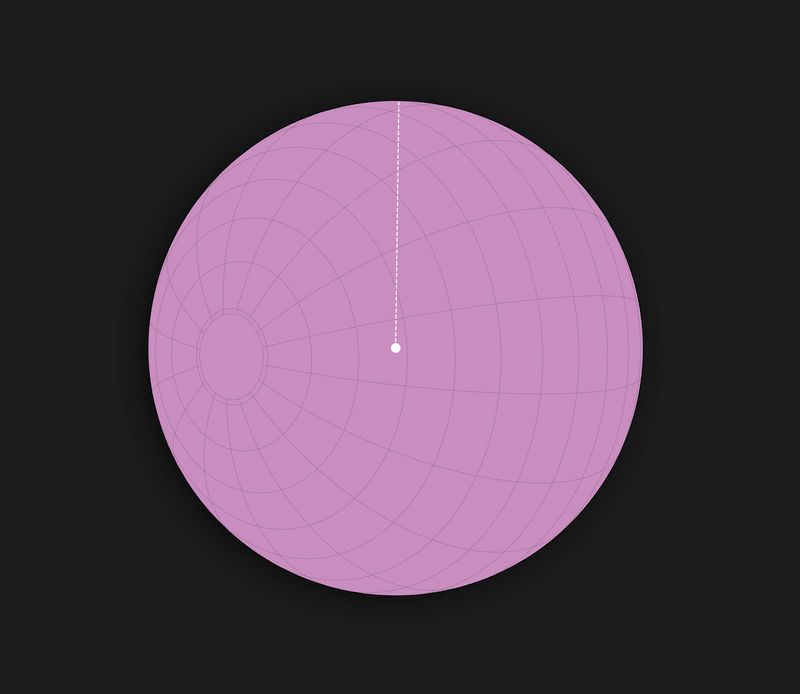

Here’s a better perspective: looking at Seattle centered on a globe, any straight line from Seattle will look like a straight line to you.

So with north pointing directly up, the path you take is a straight line directly to the right.

Being a great circle, exactly half of the path you travel is in the Northern Hemisphere, and half in the Southern Hemisphere. It swoops under Africa to arrive at Australia somewhere near Perth[2].

One way to see this would be to pin a string to Seattle on a globe, and stretch it taut over the globe. Every path from Seattle to wherever you stretch the string is a geodesic; being the shortest line on the surface of the globe to that point. Now stretch the string so that it emerges from Seattle going east: you’ll see it avoids land until Australia.

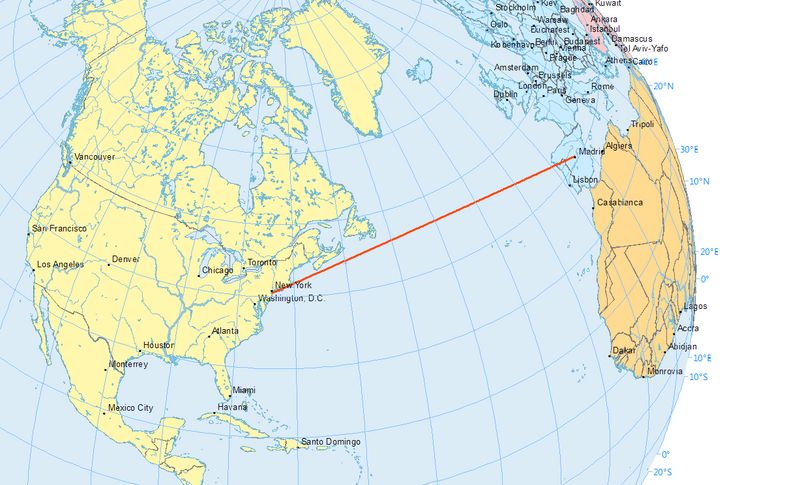

Of course, part of the trickiness here is that straight lines on the Earth are not straight lines on most 2D projections of the Earth (maps), and vice-versa.

That’s why the shortest flight path between two cities often looks unnecessarily curved on a map, such as the map you see on an airplane.

But there are some exceptions. Any straight line on a ‘gnomonic projection’ (pictured) is an arc of a great circle (straight line) on a sphere. Here’s a link to a full-res version of the image below.

But how natural to think a straight line on a more familiar map is a straight line on the surface of the Earth! And so, how natural to answer “France” over “Australia”.

I love this puzzle. Great puzzles are crafted to evoke a flash of insight, after which the answer is both clear and surprising compared to the intuitive answer. This one fits the bill. Poor puzzles feel arbitrary or like cheap tricks; they are to good puzzles as Christmas cracker puns are to good jokes.

I first saw it on Marc Ordower’s excellent TikTok page, of all places. Check it out.

Appendix: geodesics

To be pedantic, by ‘straight line’ here I really mean ‘geodesic’ — the generalisation of ‘straight line’ for curved surfaces and space as well as ‘flat’, Euclidian spaces.

A geodesic is just the shortest path between two points in a surface. If you’re placed on a surface and continually walk “forward”, by definition you will trace out a geodesic.

Some people replying to my original tweet pointed out that a straight line from the original point and direction would take you into space. This is true if we’re talking about a straight line in (3D Euclidian space). But in the original question, I say “start traveling forward, in a straight line along the Earth’s surface”. So I think it’s clear we’re talking about a straight line along a surface, which is not the same as 3D space. We’re talking about geodesics on a sphere.

But I admit that “straight line” is not exactly well-defined on curved surfaces. I’m saying “geodesic = straight line”, but someone pointed out to me a different interpretation: “straight line” is well-defined for Euclidian spaces, including the Euclidian plane (). So we can say a geodesic (or any other path) is straight just when the associated projective connection is flat, in our case when the projection of the line on the globe onto — that is, a 2D map — is straight. And that would mean that whether a path across Earth counts as ‘straight’ depends on the projection, and on popular projections (such as the Mercator projection), lateral paths would count, despite being intrinsically curved.

So maybe half a point for “France” if that’s what went through your head. Still I think “just go straight forward and don’t change direction” is the more natural reading.

I made these graphics mostly using the

basemapPython package. It’s nicely put together and documented. ↩︎Does it matter that the Earth is not a perfect sphere? It does not. It turns out the Earth is very roughly an ‘oblate spheroid’: the kind of shape you get by rotating an ellipse about its shorter axis. Here’s a coloured view of Earth’s surface height relative to its centre, as opposed to mean sea level. But Earth is only about 0.3% shorter from pole to pole compared to if it where a sphere, which is not enough to change the answer. ↩︎

Back to writing