Review of Effective Altruism – Philosophical Issues

Published 26 June 2020

Back to writingContents (click to toggle)

5,234 words • 27 min read

I recently picked up a fairly recent collection of articles on philosophical topics in effective altruism, called Effective Altruism – Philosophical Issues. I really enjoyed it, and figured it might be useful to try summarising a few chapters—in part because I think trying to explain something you’ve learned is a good test that you’ve actually understood it; and in part because there’s a chance that somebody out there might be interested in reading those summaries. So here’s my partial review, summarising the chapters I found most interesting.

1. The Definition of Effective Altruism — Will MacAskill

As a first pass, you might associate ‘effective altruism’ with three broad aspects:

- The intellectual project of using reason and evidence to identifying most effective approaches, methods, initiatives, and cause areas for doing good or improving lives — where ‘improving lives’ and ‘doing good’ and construed in broadly welfarist terms.

- The practical project (and associated global movement) of following through on (1) and volunteering significant time, money, or resources to implement such ideas and actually do good or improve lives.

- A bunch of normative claims to the effect that people have obligations to engage with either (1) or both (1) and (2).

- Weakly — if you’re planning on giving to charity with a view to doing good, you have an obligation to consider and value effectiveness.

- Strong — you have a general obligation to do good, construed in welfarist terms.

The potential surprise here is that MacAskill goes in for a definition of ‘effective altruism’ that neglects (3). This is the nutshell definition given by the Centre for Effective Altruism:

Effective altruism is about using evidence and reason to figure out how to benefit others as much as possible, and taking action on that basis.

There is, fittingly, a very practical reason for avoiding effective altruism’s normative dimensions — because ‘obligation’ talk risks being off-putting, irrespective of its truth. MacAskill cites the experience of the founders of Giving What We Can in this regard, who found that framing effective altruism as an “opportunity” to large amounts of good was, well, more effective in encouraging people to take their giving pledge than framing it as a kind of “obligation”. Whether the widerclaim that ‘obligation’ talk is always or even generally more convincing than ‘obligation’ talk remains to be seen. Ben Sachs takes up this question in chapter 9, and points out that the evidence here is wobblier than expected. You can read his article, ‘Demanding the demanding’, here.

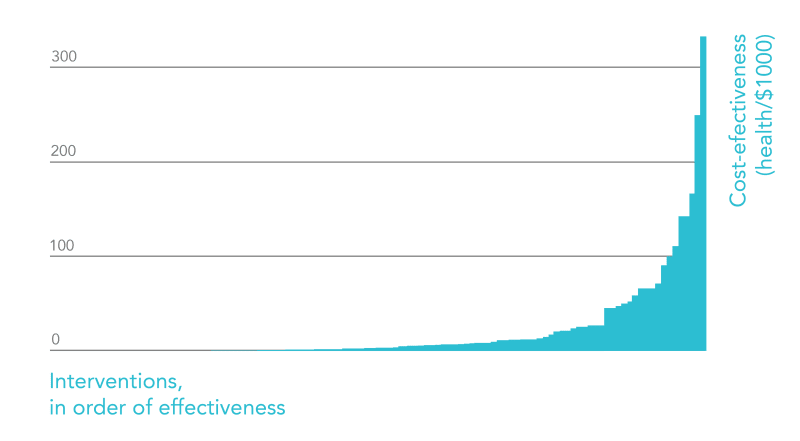

2. The Moral Imperative Toward Cost-Effectiveness in Global Health — Toby Ord

This is an early landmark for effective altruism, written by the founder of Giving What We Can. The idea is straightforward: in discussing the ethics of global health, cost-effectiveness might strike many as a technical afterthought relative to considerations of justice, equality etc. But just learning about the stark differences in cost-effectiveness between interventions in the same area —differences which often amount to many orders of magnitude — is enough to dispel this impression. The plain facts here speak so loudly that commentary or philosophising is almost unnecessary: for instance, “the least effective HIV/AIDS intervention produces less than 0.1 per cent of the value of the most effective”. It features an even clearer example which distils the key driving intuition of the priority of cost-effectiveness. I’ve used it in the past as an introduction to EA — it’s just enough to drive home the “aha” moment. It involves comparing expenditure on guide dogs with eye surgeries undoing damage from trachoma:

Suppose we have a $40,000 budget which we can spend as we wish to fight blindness. One thing we could do is to provide guide dogs to blind people in the United States to help them overcome their disability. This costs about $40,000 due to the training required for the dog and its recipient. Another option is to pay for surgeries to reverse the effects of trachoma in Africa. This costs less than $20 per patient cured… We could thus use our entire budget to provide a single guide dog, helping one person overcome the challenges of blindness, or we could use it to cure more than 2,000 people of blindness. If we think that people have equal moral value, then the second option is more than 2,000 times better than the first. Put another way, the first option squanders about 99.95% of the value that we could have produced.

Moreover, the number of lives that have been saved year-on-year by advances in global health outweighs the lives saved by other afflictions and causes not directly related to health. In other words, these striking differences in cost-effectiveness extend beyond single cause areas to comparisons between cause areas. Ord asks us to consider the lives saved since the 1930s by preventing and treating cases of diarrhea, malaria, smallpox, and by immunising against preventable diseases. These figures can be compared with the average number of deaths due to war in the 20th century. It turns out that efforts in each such class of health interventions independently saved more lives per year, on average, than would have the eradication of war: “[t]hus, in each of the four of these disease areas, our health interventions save more lives than would be saved by a lasting world peace.”

I thought this was clear and compelling enough to refer to anybody curious about the ideas which underpin effective altruism.

(That graph is from this old 80,000 Hours career guide.)

Worth noting, however, that since this paper’s original publication, the claims made in the passage about trachoma have been scrutinised. See this post for some fact checking.

3. Evidence Neutrality and the Moral Value of Information — Amanda Askell

When choosing among interventions with equivalent expected value, is there ever good reason to back the intervention with the least evidential support—i.e. the most speculative such interventions? Spoiler: yes! And for fascinating and convincing reasons!

We begin with a distinction between two features of evidence:

- Balance — whether, and to what extent, the evidence supports the claim that .

- Weight — the total amount of evidence relevant to the claim that .

Correspondingly, an agent can have a credence about some proposition , which reflects how likely they think it is that is the case — expressed by a single number ranging from 0 to 1. An agent’s credence should indicate their impression of the overall balance of evidence. However, credences do not tell us about an agent’s impression of the weight of evidence.

Suppose you’re a chess hustler in Washington Square Park and a stranger sits down in front of you. You need to quickly gauge their competence to know how seriously to take this game. So you start off with a ‘prior’ estimate of their skill (measured in ELO points) and update with every move. Your ‘prior’ here is your initial estimate of their skill with zero specific evidence, but some experience of playing other people of this person’s age, general appearance, etc. You play five moves each, and the stranger hasn’t slipped up yet. In fact, these are book moves — impressive! You begin to suspect that this person is good, so you raise your estimate from your initial prior to something high. Perhaps the estimate goes up from 1000 to 1700 points. The balance of evidence points to the stranger being good at chess. What about the weight of evidence? Well, you’ve only played five moves each; so you fully expect your estimate to wobble up or down before it begins to settle on a firmer guess. Nothing rules out this person being a grandmaster; but nothing too rules out their being a total patzer and having made a series of lucky choices. Suppose you also play a regular, who is only an amateur. On balance, your impression of their rating is lower; but the evidence you have for the regular’s ELO rating far outweighs the skilful stranger: after hundreds of games, every additional move the regular makes is less informative than the additional moves of the skilful stranger — you update your best guess of their skill level by smaller increments. To be pedantic, your credence that an opponent is some specific ELO rating is always going to be extremely low: you assign a credence to a proposition like “this person’s rating is greater than 1700”, or “this person will beat me at chess”. But that doesn’t preclude your making an estimate of their actual rating.

Chess talent is unlike charitable effectiveness, because it typically doesn’t take much to be convinced that somebody is skilled at chess. It’s cheap, easy, and near-instantaneous to gather new information: just play more games. There’s also rarely any good reason to expect somebody to be out to deceive you with hidden earpieces or the like, at least when the stakes are low. By contrast, you might have a ‘sceptical prior’ about charitable effectiveness, meaning you require a large amount of evidence to become convinced that a given charity is actually cost-effective; or as cost-effective as it claims. There are good reasons for this: gathering evidence is trickier, and faces many more confounding factors. Presumably effective charities are rarer than skilled chess players, too. It would take a 5 year-old far more accurate moves to convince you that this kid isn’t just making lucky moves!

We can draw an analogy to evidence for the effectiveness of charitable interventions. On one hand, some interventions are backed by a large amount of evidence from separate studies suggesting those interventions are very effective with near certainty. Moreover, that estimate of effectiveness is going to be relatively resilient to new evidence. On the other hand, some interventions might be associated with relatively less relevant evidence — but that evidence might suggest that those interventions are very, very effective. Suppose for simplicity that the evidence is either exactly right or else total rubbish: a false positive. The ‘expected effectiveness’ of the latter class of interventions is thus your credence that the evidence is right multiplied by the reported effectiveness of those interventions according to that evidence (by the extent to which you trust the evidence). As such, it might turn out that these two classes of intervention are equally effective in expectation. Now we have a firmer grasp of the original question: is there ever a good reason to go for one class of interventions over the other when they are equally effective in expectation?

GiveWell seems to cast a vote for favouring those interventions with more evidential support:

[W]e generally prefer to give where we have strong evidence that donations can do a lot of good rather than where we have weak evidence that donations can do far more good.

This Askell calls the ‘evidence favouring view’:

The total value of an investment is a function of the standard expected value of that investment and the weight of the evidence in support of the credences generating that expected value, such that investments supported by more evidence are better than investments supported by less evidence, all else being equal.

You might instead just be evidence neutral, where the ‘total value’ of some intervention is just its expected value. Nothing more, nothing less.

However, Askell points out that plain old measures of expected value don’t tell us about the expected value of new information; similar to how plain old credences don’t tell us about confidence — about how much we expect to update our credences in light of new information.

A ‘multi-armed bandit’ is an array of slot machines (or equivalent), each with different reward distributions. Some might reliably deliver a small payout; some might deliver rare but large payouts (and so on). The interesting problem posed by multi-armed bandits is how and how much to ‘explore’ — testing each machine to learn about its reward distribution — and when to ‘exploit’ — begin cashing in on the machine you decide has the highest expected value. As it turns out, answering that question is tricky and kind of profound. Investing in charities (and many other things for that matter) is analogous to the multi-armed bandit in the following ways: firstly, you bring about a desirable outcome with some probability; secondly, you learn something new about that outcome and that probability when you invest. This, argues Askell, is what the evidence-favouring and evidence-neutral views miss.

Incidentally, multi-armed bandits are similar (maybe the same) to a task used in psychological evaluations called the ‘Iowa gambling task’. Wrong place to start talking about all the interesting stuff you can learn from this simple test, but worth googling! You can play an online demo yourself here.

Digression aside — suppose I’m choosing between two charitable interventions A and B to invest invest a hefty sum of money. A and B have the same expected value, but there is less evidence pertaining to B. B is therefore more of a moonshot — there’s shaky evidence for a huge upside. A is a firm bet — it’s rigorously studied and documented. Suppose I choose A. I’m virtually guaranteed to have brought about some desirable outcome, but I am very unlikely to learn anything new in doing so. Suppose instead I choose B. Now, regardless of whether the intervention is successful or unsuccessful, I’m virtually guaranteed to learn something useful about whether B is worth pursuing further (since I’ve funded more of B, I’ve indirectly funded the opportunity to collect more data about B). That new information can be put to good use next time somebody is considering whether to donate to B, because I expect to update best guesses about the expected value of B and thereby help other potential donors make more informed decisions. That is why there’s often good reason to invest in the intervention with less evidence, all other things being equal.

A question remains about why effective altruists tend, in general, towards the evidence favouring view. The answer cannot be that effective altruists are generally too risk averse, given the increasing popularity of efforts to mitigate existential risks. More precisely, what is being considered here is not attitudes towards risk at all, but towards uncertainty. Putting money on red on a roulette spin involves known risk; investing in a unique and promising startup involves risk and uncertainty. A better explanation, then, is that effective altruists are irrationally averse to ambiguity: they sometimes prefer known risks with lower expected value to unknown risks with higher expected value.

4. Effective Altruism and Transformative Experience — Laurie Paul and Jeff Sebo

In the next article, Lauri Paul’s recent writing about ‘Transformative Experience’ is adapted for the context of effective altruism. The general idea is that certain experiences or changes are dramatic enough that (i) actually undergoing them is a necessary condition for knowing what they’re like; and (ii) you emerge with (substantially) new preferences, sense of identity, or beliefs. For instance, it is virtually impossible to make a fully informed decision about having a child or getting married if you haven’t before been married or had children. As applied: how should an aspiring effective altruist plan her career if she lacks the experience to make an informed decision, nor the time to try every alternative? Should she “earn to give” if her future hedge-fund-manager-self eventually writes-off her original intention as naïve, youthful optimism?

This is an important thought! And those new, transformed, preferences could go both ways. Suppose I’m choosing between career options A and B. Let’s say—purely hypothetically!—that I’ve just graduated and need to choose between grad school and some kind of work. In that case, I might expect to be confident I made the right decision irrespective of whether I chose A or B. If I continue my studies, I’ll make friends with more academics, and get familiar and comfortable with the academic life. If I choose to work, I’ll get comfortable and familiar with working… There are absolutely all kinds of reason in addition why I might expect to endorse my decision. Conversely, there are some (perhaps rarer) decisions between options when I can expect to regret my decision. Here’s the ever-cheery and nuanced Kierkegaard:

Marry, and you will regret it; don’t marry, you will also regret it; marry or don’t marry, you will regret it either way. Laugh at the world’s foolishness, you will regret it; weep over it, you will regret that too; laugh at the world’s foolishness or weep over it, you will regret both… This, gentlemen, is the essence of all philosophy.

One possible way to make such big career decisions is to partake in smaller-scale ‘experiments in living’ (to use J.S. Mill’s phrase). But this doesn’t obviously solve the problem at all:

You can dip your toes in the water by taking classes in finance, taking a summer internship in finance, spending time with people who work in finance, and so on, and, as a result you can collect evidence about yourself in this situation without yet committing to this path. This can certainly help. But insofar as these experiments are informative, they may also be transformative: You may already be changing your preferences as a result of the experience.

Thus, it is often impossible to engage in such an experiment in living, and emerge the other side to make a meaningfully impartial decision. On the other hand, it is often useless to talk to somebody who themselves have experienced an option you are considering, in cases where the information they’re trying to impart can’t really be understood by anyone who hasn’t themselves experienced that option. Case in point: try asking someone what it’s like to have kids: there’s a good chance they’ll tell you something like “you’ll understand when you have them”.

The musician Fats Waller summarises this predicament nicely in his oft-quoted remark about the definition of jazz: “…if you hafta ask, you ain’t never gonna know!”.

This made me curious to check out Paul’s book. She also recently gave an interview on the EconTalk podcast, which you can check out here.

6. A Brief Argument for the Overwhelming Importance of Shaping the Far Future — Nick Beckstead

Next, Nick Beckstead effectively presents a SparkNotes summary of his thesis arguing for the overwhelming importance of the far future. This piece made tangible an idea which is often to hard to grasp intuitively, even if you find it conceptually watertight: that the value of the long-term future is staggeringly huge in expectation, and should factor into our moral priorities with corresponding urgency and weight. Here’s the back-of-the-envelope calculation Beckstead proposes: let’s say (conservatively) humanity has a 1% chance of surviving for another billion years. This will almost certainly involve developing the technology for colonising space—so conditional on surviving that long, let’s say humanity again has at least a 1% chance of spreading through the stars and thereby surviving for 100 trillion years. The expected duration of humanity’s future lifespan is therefore at least 1% × 1% × 100 trillion = 10 billion years. Like Toby Ord’s comparisons of cost effectiveness, that figure alone might be enough to make the longtermist case.

So humanity’s future is enormously valuable in expectation. Should we care? What kind of things should we care about? And what should we do about that?

We should care because, all other things being equal, depriving people of good things in the future is bad. Suppose my friend books a ticket to two concerts: one tomorrow, one in a year’s time. I could prevent him going to either one today by removing all trace of his having bought the ticket (I don’t know, maybe I’m a hacker or something). Would it be much worse to delete one ticket over the other? Not obviously. Similarly, Parfit gives an example of burying some broken glass in a forest path. Consider two cases:

- A child steps on the broken glass in 10 years time.

- A child steps on the broken glass in 110 years time.

Is (1) obviously much worse than (2)? Suppose you thought we should ‘discount’ future welfare by some fixed amount year-on-year. Suppose that the annual discount rate was 5%. Well, if you run the numbers, this apparently modest discounting entails that (2) is over one hundred times less bad than (1). So it looks like discounting future welfare is not a very sensible thing to do, and that we should therefore care about preserving and/or bringing about a prosperous and valuable future for humanity.

Some people object to this line of thought by arguing that failing to bring about nice things for future people who are not yet born cannot be a bad thing, because it doesn’t affect any actual people. If I somehow have the opportunity to make sacrifices today to save lives in the far future and decide not to take it, nobody is harmed precisely because those possible people never end up existing. This is called the ‘person-affecting view’; and Beckstead gives it short thrift in his article. One way of seeing why any strong, literal version of the view can’t quite be right is to notice that it would clearly be a bad thing if everyone just decided to stop having children one day, and humanity came to an end. Yet, the person-affecting view struggles to make sense of why this is so bad.

Given that we should care about the far future, what kind of specific things should that involve care about? One answer is ‘existential catastrophes’ — permanently curtailing humanity’s potential. Since that potential is so enormous, an ‘existential catastrophe’ would be much worse than most people think. Parfit again gives a good illustration. Consider the difference between:

- Peace.

- A nuclear war that kills 99% of the world’s existing population.

- A nuclear war that kills 100%.

How much worse is (2) than (1), and (3) than (2)? If your answers are “a lot” and “about 1%” respectively, you’re missing something. In (2), there’s a good chance humanity could recover to similar levels and standards of living after (even a very long) time. In (3), there’s no chance whatsoever that humanity could recover, because they’re all dead. Thus, the expected value of humanity’s future in (3) is zero; in (2) it remains large. So (2) is certainly a lot worse than (1), but (3) is much more than 1% worse than (2) in expectation! So there’s a (slightly counterintuitive) reason to really care about avoiding existential catastrophes.

Finally, what should we do about it? One obvious answer is to divert more resources than we presently do towards mitigating existential risks. See Toby Ord’s book The Precipice for more (and some facts I collected from the book here). There’s also a case for thinking that subtler kinds of progress matter:

Perhaps some forms of social and moral progress have long-lasting effects on our long-term trajectory, with inputs from people in many directions. For reasons like this, I think that many people improve our expected long-term trajectory in subtle ways like this without knowing it and thereby do much greater expected good than one might think when contemplating these arguments, and much greater expected good than they realize themselves.

7. Effective Altruism, Global Poverty, and Systemic Change — Iason Gabriel and Brian McElwee

In “Effective Altruism, Global Poverty, and Systemic Change”, Iason Gabriel and Brian McElwee argue that the effective altruism movement has largely overlooked a class of causes that sit somewhere between existential risk reduction (see previous) and narrowly targeted, epistemically secure interventions in global health. The former class addresses potentially enormous payoffs or losses with correspondingly slim probabilities and / or confidences. The latter deals with smaller payoffs, but with fewer unknowns and high confidence of success—being backed by fairly unequivocal kinds of empirical feedback. Addressing global poverty via systemic change falls somewhere in the middle along both dimensions. The authors cite books like The Great Escape, Why Nations Fail, and Blood Oil as identifying such neglected systemic causes of poverty—like global supply chains sustaining authoritarian regimes, rent-seeking and ‘extractive’ political institutions, and tax evasion which “deprives countries of vast capital flows that could be used to improve the lives of their citizens”. The authors also note, and the historical record apparently bears out, that few equivalently serious systemic social problems are tackled without advocacy movements and targeted campaigns. Yet, targeted movements pulling on the right levers can result in disproportionately significant and cost-effective outcomes. I learned, for instance, about one such initiative called Global Witness:

...founded in 1993 to help tackle illicit financial flows to authoritarian regimes, including the trade in blood diamonds. Operating with an annual budget of several thousand dollars, the organization spearheaded efforts to establish the Kimberly Process for diamond certification and was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize as a result of its efforts. More recently, it was the driving force behind the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), an endeavour which has led corporations to publicize trillions of dollars of previously hidden financial transactions.

So seeking out systemic change seems (i) somewhat tractable and achievable; (ii) promises huge potential payoffs, and (iii) answers the charge that more targeted and practical interventions (bed nets, nutritional supplements…) ‘plaster over’ symptoms of (unaffected or even indirectly reinforced) systemic causes. Indeed, it may be the case that some of these interventions in fact do harm by inadvertently reinforcing harmful systems even while successfully responding to immediate needs. Here’s Deaton: “If [development] were so simple, the world would already be a much better place. Development is neither a financial nor a technical problem but a political problem, and the aid industry often makes the politics worse.”

It isn’t immediately clear, then, why effective altruists are not on the whole more interested in systemic change. One explanation—mere risk aversion—clearly won’t stick, given the vanishing probabilities involved in existential-risk reduction. Gabriel and McElwee point instead to an aversion to taking political sides (broadly construed). Whatever the reason, the conclusion seems right:

[T]he greatest positive impacts on the world can be achieved not through iterated small-scale interventions, but rather through systemic initiatives that alter the rules within which actors operate and that challenge the values that underpin them. Exerting even small leverage over very large systems could in principle have much greater impact than efforts to optimize within the status quo.

These sentiments have since been repeated in a post on the EA forum by John Halstead and Hauke Hillebrandt. The authors argue:

- “Prominent economists make plausible arguments which suggest that research on and advocacy for economic growth in low- and middle-income countries is more cost-effective than the things funded by proponents of randomista development.

- Effective altruists have devoted too little attention to these arguments.

- Assessing the soundness of these arguments should be a key focus for current generation-focused effective altruists over the next few years.

- Improving health is not the best way to increase growth.

- A ~4 person-year research effort will find donation opportunities working on economic growth in LMICs which are substantially better than GiveWell’s top charities from a current generation human welfare-focused point of view.”

The thought is fairly simple: economic growth is, overwhelmingly, the factor that most reliably improves (and has improved) the quality of life for the most people. The interventions best evidenced by RCTs and other empirical data, and thus advocated by effective altruists and charity evaluators like GiveWell, operate not with a view to fostering economic growth but e.g. improving health. To be sure, preventing unnecessary deaths due to disease, fortifying food with essential nutrients, etc is not orthogonal to economic development; but it would be surprising if those things were the most reliable ways of enabling low-income countries to grow. The upshot, then, is that EAs would do well to (i) pay attention to existing research about growth and development; and (ii) possibly invest more resources in doing that research themselves. That’s all fairly tentative, as the authors stress, but plausible enough to take seriously.

The authors repeat Deaton’s point in articulating the more extreme and concerning worry that “effective altruist organizations could do more harm than good, if the public responded to their recommendations by withdrawing support from systemic causes—such as efforts to promote human rights or combat climate change—adopting the view that the only interventions worth backing are those that show promise through testing which meets high-epistemic standards.”

If that sounds interesting, you might also like to check out Larry Temkin’s 2017 Uehiro lectures on the topic; particularly lecture 3.

Anyway, I think this was my favourite piece of the bunch—challenging and convincing. Read it!

12. The Hidden Zero Problem: Effective Altruism and Barriers to Marginal Impact — Mark Budolfson and Dean Spears

In this article, Mark Budolfson and Dean Spears point out a simple and worrying way in which small individual donations might sometimes have no marginal impact whatsoever, despite the effectiveness of the recipient charities. This is when wealthy (i.e. billionaire) donors make commitments to ‘top-up’ the funds of that charity whenever it falls short of its fundraising goal. If, for illustration, you choose to donate £100 to AMF, this might just mean that some billionaire coughs up £100 less at the end of the year—money which likely instead falls into some ‘saving for a new luxury item’ jar. In this way, the counterfactual effect of donating to effective charities backed by ‘top-up’ pledges from wealthy donors may be to “merely to transfer money to a billionaire in the United States, and accomplish nothing for the global poor.”

There were also a handful of articles introducing philosophical concepts that were mostly new to me — including the ‘possiblism’ vs ‘fallibilism’ dispute, the notion of ‘membership duties’ derived from citizenship and the resulting ‘cooperative utilitarianism’, the conditions under which one has satisfied duties to assist, the difference between ‘sympathy’ and ‘abstract benevolence’, and the so-called ‘callousness objection’. All equally deserving of comment, but this review is already too long.

I heartily recommended this book for anybody curious about live and nuanced issues in effective altruism beyond the standard arguments for and against. Five stars!

Back to writing