Book reviews (ongoing)

Published 1 January 2026

Back to writingContents (click to toggle)

30,507 words • 153 min read

This is a mirror of my written book reviews on Goodreads.

They are generated using the .csv file of reviews which Goodreads lets your export. Here’s the code I used if you’re interested.

All by year

2026

- Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed

- The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

2025

- John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs

- Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection

- Law’s Order: What Economics Has to Do with Law and Why It Matters

- The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World’s Most Coveted Microchip

- The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century

- If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All

- Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future

- After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People

- The Passage of Power (The Years of Lyndon Johnson, #4)

- And the Roots of Rhythm Remain: A Journey Through Global Music (ZE Series, 6)

- Legal Systems Very Different From Ours

- Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology (Anchor Library of Science)

- The End of History and the Last Man

- One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger

- Penance

2024

- The Edge of Sentience: Risk and Precaution in Humans, Other Animals, and AI

- Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa

- Abundance

- Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy

- The Enigma of Reason

- On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

- Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI

- A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World

- Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life

- What Is Life? with Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches

- Cognitive Gadgets: The Cultural Evolution of Thinking

- Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

- Modern Principles of Economics

- World Within a Song: Music That Changed My Life and Life That Changed My Music

- Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World

- Infrastructure: The Book of Everything for the Industrial Landscape

- The Rise of Modern Japan

- The Coming Wave: Technology, Power, and the Twenty-first Century’s Greatest Dilemma

- Great Mambo Chicken And The Transhuman Condition: Science Slightly Over The Edge

- Elements of Jazz: From Cakewalks to Fusion

2023

- Poor Charlie’s Almanack: The Essential Wit and Wisdom of Charles T. Munger

- Bach and the High Baroque

- The Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia

- Thinking In Systems: A Primer

- Radical Acceptance: Embracing Your Life With the Heart of a Buddha

- Radical Compassion: Learning to Love Yourself and Your World with the Practice of RAIN

- The Son Also Rises: Surnames and the History of Social Mobility

- Elon Musk

- Kitchen Confidential: Adventures in the Culinary Underbelly

- The Imagineers of War: The Untold Story of DARPA, the Pentagon Agency That Changed the World

- How Minds Change: The Surprising Science of Belief, Opinion, and Persuasion

- The Future of Geography: How Power and Politics in Space Will Change Our World

- The Making of the Atomic Bomb

- How to Achieve Financial Independence and Retire Early

- Moral Mazes: The World of Corporate Managers

- Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence

- Don’t Be a Feminist: Essays on Genuine Justice

- Labor Econ Versus the World: Essays on the World’s Greatest Market

- The Pattern on the Stone: The Simple Ideas that Make Computers Work

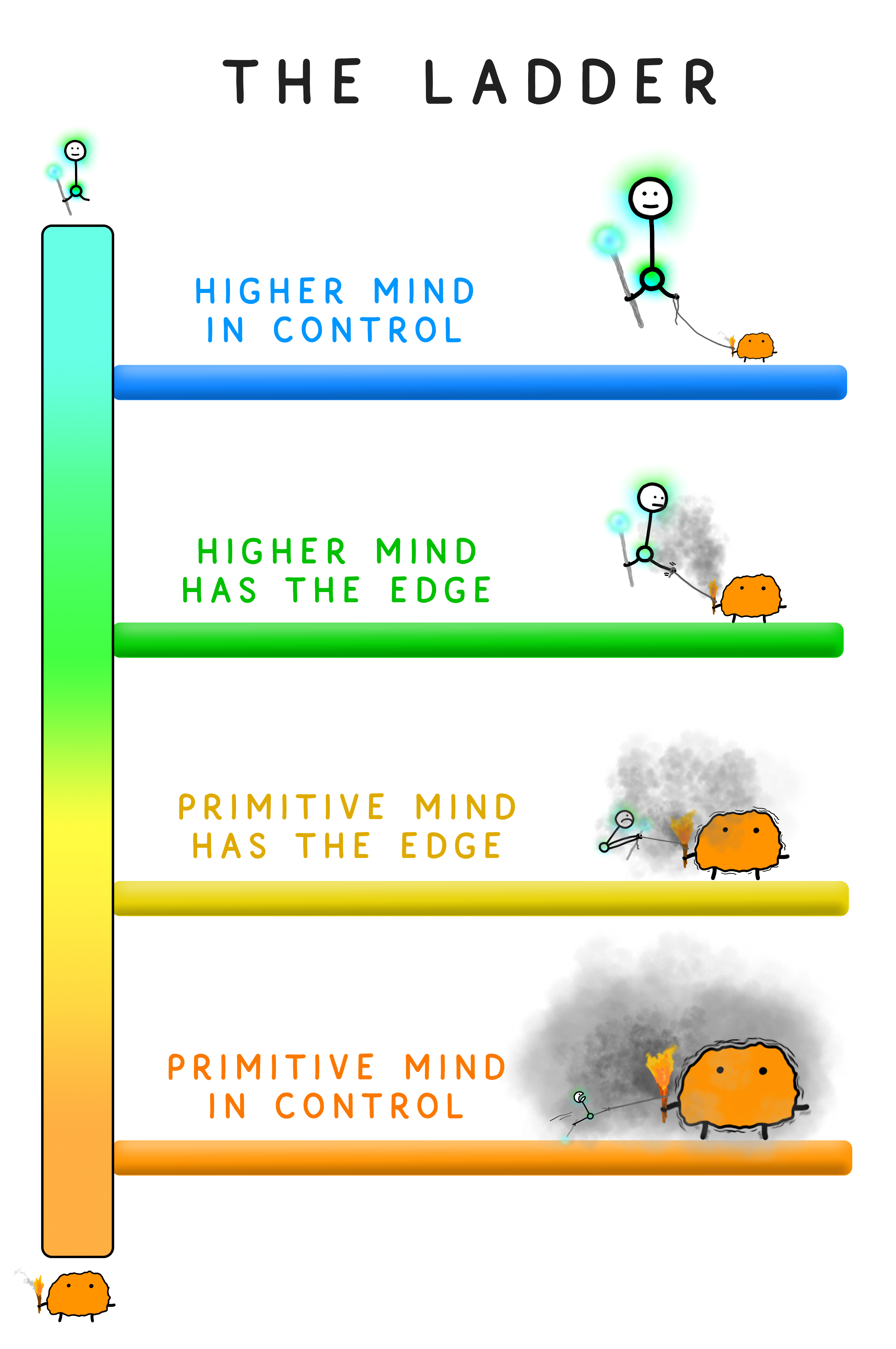

- What’s Our Problem?: A Self-Help Book for Societies

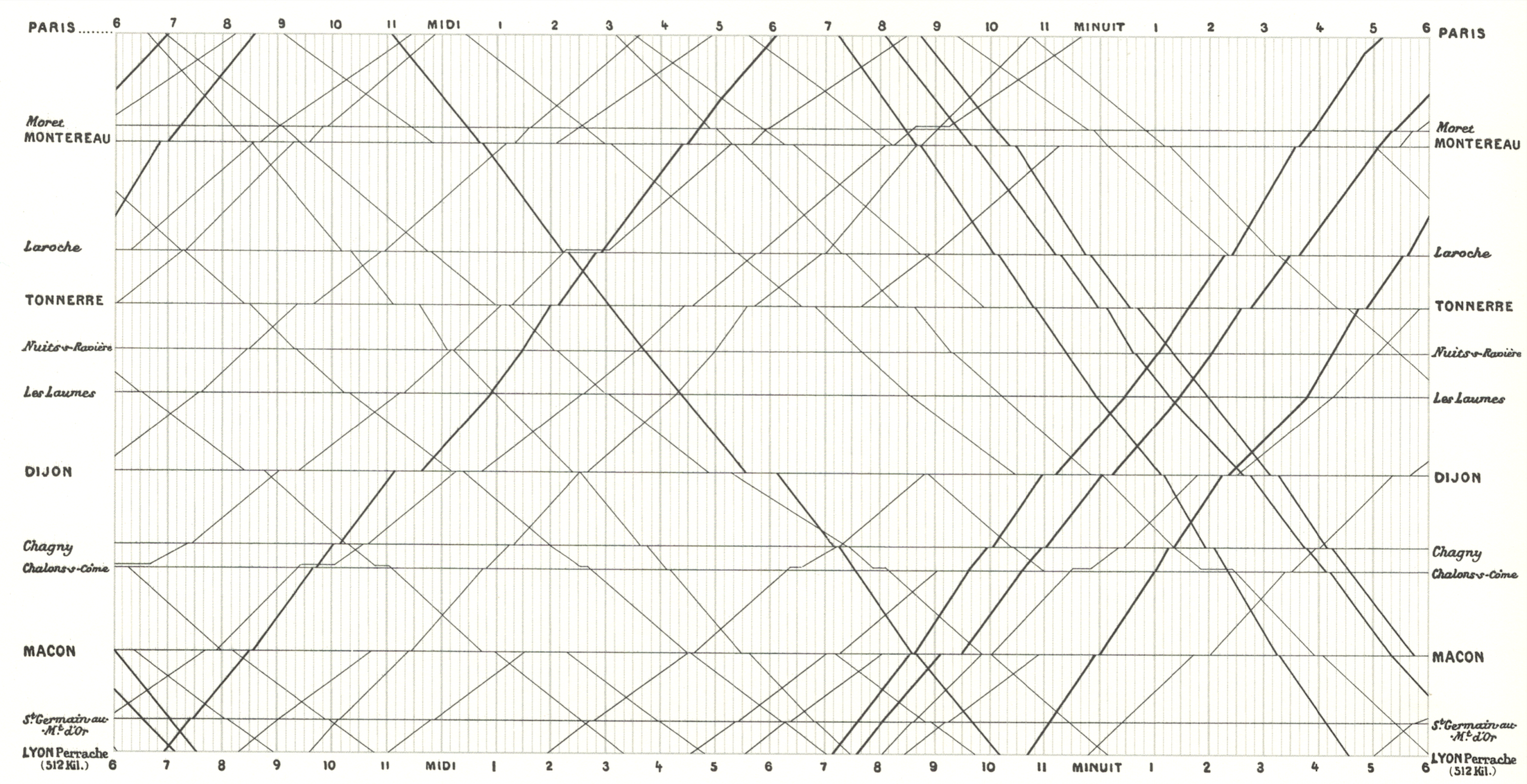

- The Visual Display of Quantitative Information

- The Hacker and the State: Cyber Attacks and the New Normal of Geopolitics

- Functional Training and Beyond: Building the Ultimate Superfunctional Body and Mind

- Tracers in the Dark: The Global Hunt for the Crime Lords of Cryptocurrency

2022

- Avoiding the Worst: How to Prevent a Moral Catastrophe

- Weighing Goods: Equality, Uncertainty and Time (Economics and Philosophy)

- How the World Really Works: A Scientist’s Guide to Our Past, Present and Future

- Billions & Billions: Thoughts on Life and Death at the Brink of the Millennium

- American Kingpin: The Epic Hunt for the Criminal Mastermind Behind the Silk Road

- What We Owe the Future

- Whole Earth: The Many Lives of Stewart Brand

- Big History: The Big Bang, Life On Earth, And The Rise Of Humanity

- How to Prevent the Next Pandemic

- Talent: How to Identify Energizers, Creatives, and Winners Around the World

- Who We Are and How We Got Here: Ancient DNA and the New Science of the Human Past

- Cosmos

- The New Fire: War, Peace, and Democracy in the Age of AI

- How to Live: 27 conflicting answers and one weird conclusion

- History of the Ancient World: A Global Perspective (The Great Courses)

- The Doomsday Machine: Confessions of a Nuclear War Planner

- Energy and Civilization: A History

- Valley of Genius: The Uncensored History of Silicon Valley (As Told by the Hackers, Founders, and Freaks Who Made It Boom)

- Four Thousand Weeks: Time Management for Mortals

2021

- The Man from the Future: The Visionary Life of John von Neumann

- Human Frontiers: The Future of Big Ideas in an Age of Small Thinking

- Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion

- Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity

- The WEIRDest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous

- The Good Ancestor: A Radical Prescription for Long-Term Thinking

2020

- The Very Hungry Caterpillar

- Science Fictions

- The Story of Human Language

- Soonish: Ten Emerging Technologies That’ll Improve and/or Ruin Everything

- How to Listen to and Understand Great Music

- Moral Uncertainty

- Effective Altruism. Philosophical Issues

- Natural Justice

- The Cuckoo’s Egg: Tracking a Spy Through the Maze of Computer Espionage

- The Precipice

2019

2016

2026

Skunk Works: A Personal Memoir of My Years at Lockheed

Ben R. Rich (1996) • ★★★★☆ • Jan 26 • Link to book ↗

Rollicking stories of defence R&D from c. 1950–80. Cold War, Vietnam War, Gulf War; Dragon Lady, Blackbird, Nighthawk; jet fuel, testosterone.

A favourite anecdote:

We were issued [cyanide pills] in case of capture and torture and all that good stuff, but given the option whether to use it or not. But [the pilot] didn't know the cyanide was in the right breast pocket of his coveralls when he dropped in a fistful of lemon-flavored cough drops. The cyanide pill was supposed to be in an inside pocket. Vito felt his throat go dry as he approached Moscow for the first time […] so he fished in his pocket for a cough drop and grabbed the cyanide pill instead and popped it into his mouth. He started to suck on it […] and spit it out in horror before it could take effect. Had he bit down he would have died instantly and crashed right into Red Square.

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

Robert A. Caro (1975) • ★★★★★ • Jan 26 • Link to book ↗

Justice by way of painstaking journalism.

Whitman, ‘Crossing Brooklyn Ferry’ —

Others will enter the gates of the ferry and cross from shore to shore, Others will watch the run of the flood-tide, Others will see the shipping of Manhattan north and west, and the heights of Brooklyn to the south and east, Others will see the islands large and small; Fifty years hence, others will see them as they cross, the sun half an hour high, A hundred years hence, or ever so many hundred years hence, others will see them, Will enjoy the sunset, the pouring-in of the flood-tide, the falling-back to the sea of the ebb-tide.

Caro —

But the last smile was Moses’. [F]ifty-two Astoria residents who had come down to the Astoria pier for old times’ sake (plus twelve other persons who just wanted to get to Manhattan) boarded the Rockaway for its last round trip across the river […] As the Rockaway [ferry], having completed the round trip, bumped into the Astoria slip for the last time, they sang “Auld Lang Syne.” Then, as the old tub left for the Brooklyn pier where she was to be laid up, her captain blew three long, dolorous whistle blasts of farewell. Hardly had the last note faded when it was succeeded by dull heavy thuds—the pound of Moses’ pile driver, tearing the ferryhouse down again.

As far as I can tell, the name of Jane Jacobs isn’t mentioned once in the main text. Apparently Caro wrote an entire chapter on the Jacobs / Moses feud, a chapter he was proud of; but it was cut for space along with some other 400,000 words or so.

Still Caro was greatly influenced by The Death and Life of Great American Cities, though they only got speak after the book was published —

Jane had moved to Toronto, but some years after The Power Broker came out, Mary called and said Jane was coming to New York and would like to meet me […] And I remember that Jane Jacobs and I sat the whole evening on the sofa talking.Of course, what we wound up talking about was Robert Moses. He didn’t like either one of us very much. We had a great talk. It turned out that we each had a question that we wanted to ask the other. Jane wanted to ask me what it was like to meet him. I wanted to ask her, what it was like to beat him.

2025

John & Paul: A Love Story in Songs

Ian Leslie (2025) • ★★★★★ • Dec 25 • Link to book ↗

Made me smile more than any book this year. Reading about the shuffling in and out of potential band members, the Hamburg days, Paul nearly dropping out, Decca declining to sign them because “guitar groups are on the way out”; and knowing it’s all going to come together, that these are the makings of a miracle.

Like most of their songs, The Beatles did not outstay their welcome. They were effectively a covers band in '60, by '66 John was telling the press they were “more popular than Jesus”, and by late '69 they had all but cemented their break-up. When they wrapped up their last session all together in the titular Abbey Road studios, when all their music was behind them, John was 29 years old and Paul was 27 (Ringo 29, George 26). Hard to even contemplate!

The popular imagination has held Paul’s and John’s reputations in balance, so picking your “favourite Beatle” is understood to be like a personality test or guessing your Harry Potter house. Between the two de facto leaders: John was bohemian, Paul was bourgeois; John was acerbic, Paul charming; John’s music leaned psychedelic and edgy, Paul’s songs were music hall and balladry; John was politically radical, Paul domestic and commercial. John perhaps the deeper and more interesting personality, Paul shallower but perhaps more productive. J&P were mirror images, enantiomers.

But no, there is a clear answer. Paul should be your favourite Beatle.

George Martin said he was the one who kept the band functioning. He showed up on time, turned threads of ideas into finished songs; did the schlep. When Brian Epstein died in '67, Paul became the driving force. He led the band and held it together for another few years, as much a manager as a musician.

And he continued to produce music since the break-up with no real let-up. Tyler Cowen:

Perhaps he has written more hit songs than anyone else. He brought the innovations of Cage and Stockhausen into popular music, despite having no musical education and growing up in the Liverpool dumps. His second act, Wings, sold more records in its time than the Beatles did.

He wrote good and often truly great music across “heavy metal, blues, music hall, country and western, gospel, show tunes, ballads, rockers, Latin music, pastiche, psychedelia, electronic music, Devo-style robot-pop, drone, lounge, reggae”. He almost single-handedly wrote the B-side medley on Abbey Road. He is also funny and he was a vegetarian long before it was easy.

The Beatles are hard to appreciate on their own terms because they are so iconic and overexposed, and it’s fun to get to re-appreciate them.

Everything Is Tuberculosis: The History and Persistence of Our Deadliest Infection

John Green (2025) • Oct 25 • Link to book ↗

TB has killed more than any pathogen ever, likely more than all war and conflict combined, more than a billion people. Hundreds of millions of people are infected right now, at least in a latent or subclinical form.

If you’re a nonfiction writer and have latitude to choose your subject, I think it’s a good thing to choose one of the most important topics in the world, especially when almost nobody knows much about it. So: major props to JG.

It’s a book about the history of the disease (“white plague”, “consumption”) and how it was romanticised and racialised, about patients JG came to know (mostly in Sierra Leone), about how the disease is treated in the poor countries where it is most endemic; and how the world can do better.

It’s readable, moving, interesting, and personal. I loved The Anthropocene Reviewed and this has the same mix of factoids and pathos.

If I have gripes, it’s that JG doesn’t seem so compelled by scale, scope, numbers, trends. He says as much: that he’s writing the book because of the few individuals who he met and formed close relationships with (like Henry Reider, who has a great YouTube channel). But perhaps one reason (especially tropical) diseases responsible for the most easily avoidable deaths are so overlooked is because those who can do something about them do not or cannot easily grasp their sheer terrible scale. Yes, it is harder to write narrative nonfiction about faceless statistics, but neglecting the numbers undersells the importance.

I also wish there were a little more material on how to better prevent and treat TB: I can’t remember if the RATIONS study gets a callout, but that seems like a big deal. Vaccines, too. There are no approved candidates right now, but a handful in preclinical (animal / cell line) trials, and a few have passed or are currently in Phase II and entering Phase III (in particular the M72 candidate). Again, that’s potentially huge! And I don’t think it gets discussed. Instead, the major focus of blame and responsibility is placed on things like the colonial legacies of countries with high TB incidence, or poverty in general, and the greed of the pharmaceutical companies that price those countries out, by insisting on huge margins above cost. Those things are obviously real and important factors, but I would speculate that efforts directed towards addressing them (in order to move the needle on TB) might ultimately help fewer people with the disease less quickly, than more targeted and wonkish (if less narratively satisfying) initiatives. I do feel a little bad saying that because overall it’s a great book and JG deserves massive kudos.

Law’s Order: What Economics Has to Do with Law and Why It Matters

David D. Friedman (2001) • ★★★★☆ • Oct 25 • Link to book ↗

There is, however, one conjecture about law that has played a central role in the development of law and economics. This is the thesis, due to Judge Richard Posner, that the common law, that part of the law that comes not from legislatures but from the precedents created by judges in deciding cases, tends to be economically efficient.

This is a book about that idea. The writing is terse, idea-dense, classic style. Sometimes, deliberately or not, it’s hilarious, because of the degree to which you must suspend normal intuitions about justice, fairness, basic decency (in the attempt to explain those intuitions in terms of efficiency). There is, for example, a serious and protracted discussion of why the appropriate punishment for every crime should not be to impose the death penalty with a probability proportional to the severity of the crime, and otherwise to free the accused.

I recommend reading the epilogue, which is wonderful.

The Thinking Machine: Jensen Huang, Nvidia, and the World’s Most Coveted Microchip

Stephen Witt (2025) • ★★★★☆ • Oct 25 • Link to book ↗

Huang is not the easiest subject for a biography: he doesn’t like to philosophize, he doesn’t indulge in psychoanalysis, he doesn’t seem to like talking about himself at all. Personality-wise, think the opposite of Oppenheimer. “His hobbies”, per a colleague, “are work, email, and work.”

But you should know:

[I]t was not an exaggeration to suggest that Huang had personally saved the American economy from recession. The US stock market, over the course of Nvidia’s rise, had pulled away from markets in Europe and Asia. Almost all of that outperformance was attributable to AI. Nvidia’s $3 trillion market capitalization purportedly represented the expected value of the company’s future earnings—but it was really a giant, GDP-sized bet on the capabilities of this single sixty-one-year-old man.

I really enjoyed this one. Nvidia aside, I thought it did a great job capturing that mad ascendency of AI capabilities, investment, excitement, and fear, from around 2020 onwards.

The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century

Alex Ross (2007) • ★★★★☆ • Oct 25 • Link to book ↗

It’s a sweeping book of 20th c. musical history and biography. More exactly it’s about what you might call concert or ‘classical’ music: Wagner, the Rite, “serialism”, impressionism and expressionism, musique concrète, 4’33". To be contrasted with ‘popular’ or ‘commercial’ music.

The blurb to the book says it is about “modern music”. Apparently the world of (let’s just say) modern classical music uses language like “music” in this bizarrely hermetic way to implicitly exclude basically all popular music unless stated otherwise. I think there’s something telling about that: “music” really did mostly refer to classical or concert music around the turn of the 20th century.

But then, gradually, everyone stopped listening. Ross compares contemporary classical music with Debussy’s ‘sunken cathedral’; and the rest of the book is about the cathedral sinking.

There is also a sense of identity crisis; of being stuck between more traditional ‘tonal’ music (too reactionary, too much like pastiche now), or keeping pace with the avante-garde and its new theories (but is that progress? Who will listen to this stuff in 50 years?)

This paragraph from nearer the end of the book puts it really well:

Although vast quantities of music are being written down day by day […] few of them have found an audience outside a relatively limited clique of new-music fanciers. Some specialize in "music for use," writing for church choirs or collegiate wind bands or the soundtracks of video games. The majority make a living by teaching composition, and their students usually become teachers themselves. They may sometimes ask, with the title character of Hans Pfitzner's Palestrina, "What is it for?" They have read in books that their forebears humbled kings, electrified crowds, forged nations. Sooner or later they realize that modern popular culture has no place for a composer hero.

A lot has been written about the “modernist turn” in literature, music, art generally. One story I sometimes here is that, when artistic products become mass-producable, they split apart. Originally the audience is a kind of cultural elite with the time and money to appreciate their artistic medium of choice (concerts, theatre, opera, etc.) — their taste becomes “highbrow”. Then there is an explosion in popular stuff, and whether or not the old audiences sniff at it, it grows up mostly all on its own, differentiating into a thousand sub-genres and so on. And then there is polarisation: audiences for classical concerts shrink because some would-be concert goers are now going to jazz or rock concerts, so the classical stuff caters to an even narrower audience. When it became possible and then increasingly affordable to make movies, we didn’t lose theatre or arthouse cinema, but we also got YouTube and Marvel. “Whither Tartaria?” asks Scott Alexander, who comes up with many other stories.

John Cage: “We live in a time I think not of mainstream, but of many streams, or even, if you insist upon a river of time, that we have come to a delta, maybe even beyond delta to an ocean which is going back to the skies”. That’s also a theme in Joe Boyd’s awesome And the Roots of Rhythm Remain. So maybe the more optimistic reading is that modern classical seems to fade into irrelevance only because it dissolved into every other musical form.

Also, maybe I’m overly critical here because I admit I have tried to ‘get’ (as in, ‘enjoy’) many of the composers in this book and failed. Maybe I should try harder.

If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies: Why Superhuman AI Would Kill Us All

Eliezer Yudkowsky (2025) • ★★★☆☆ • Sep 25 • Link to book ↗

It’s a book-length case for the MIRI/Yudkowsky worldview on AI for a general audience.

Writers on AI are often but not always either cranks and grifters. Cranks’ ideas flow from quirky of their psychiatry, not serious thinking, so they’re typically not worth engaging with. Grifters see some topic accumulate hype, they rush to position themselves as experts, and dispense underbaked takes. Y&S are neither, they really are serious about all this: they have been writing about these questions forever, they have engaged with a ton of criticism from smart people, they sincerely believe what they write, and they are motivated by those beliefs (not the sheer joy of shocking people, or the prospect of a glamorous press tour). Through their writing to date they have both taught me a whole lot, especially EY.

However: I found the writing style fairly a bit grating; often smug or sententious.

Part of me thinks: I’ve missed the point if I’m criticising such a huge-if-true argument for its writing style — you wouldn’t criticise Einstein for bad grammar. But I do think it matters because Y&S are trying to persuade people of their views, and good writing persuades. I note opinions seem to vary here.

Take this tweet (with an image of the book attached) — “Reading this in public and shaking my head ever so slightly — but also frequently nodding — so people know I think the authors are absolutely right about the core point that ASI is an urgent and under-appreciated risk but also they’re overconfident and too pessimistic”. That about captures how I felt. These are important arguments to consider, but I found myself getting frustrated at the unwillingness to consider details, the willingness to ‘shadowbox’ (it seemed to me) shallow counterarguments, and the weird gnomic insistence on arguing through parables and allusions. In particular, the central argument runs through an analogy with evolution by natural selection. There are some obvious disanalogies between training AIs and evolution which didn’t seem well-addressed. Maybe it’s in the list of appendices.

Is this the narcissism of small differences? The Judean People’s front think AI extinction risk is 90%, the People’s Front of Judea think it’s 20% or 1%, surely what matters is that the rest of the world doesn’t isn’t doing anything about it. In this case I think such differences do matter — those who fret about AGI can agree the stakes are very high indeed, and meaningfully disagree on what to do, and worry each other’s proposals could backfire.

On the other hand: I’m not the intended audience. Maybe it’s not important that I wasn’t blown away by the precise arguments or policy proposals. There is a hope that moments like this puncture some pluralistic ignorance about levels of concern, that whatever the technical and policy answers, those who matter can say more publicly “we’re not sure things are going to be ok vis a vis AI and humanity, and we’re not ok with that”, without fear of weirdness or doom-mongering. I’m glad the book exists.

Breakneck: China’s Quest to Engineer the Future

Dan Wang (2025) • ★★★★☆ • Sep 25 • Link to book ↗

More impressionistic than I expected, really a blend of very perceptive travel writing and narrative-driven history, more than a sustained argument. But it works very well.

After the Spike: Population, Progress, and the Case for People

Dean Spears (2025) • ★★★★☆ • Sep 25 • Link to book ↗

You stand now at the top of the Spike with 8 billion others. The story of the future starts with understanding the fact that most of those 8 billion others don't (or didn't, or won't, once they grow up) aspire to parent very many children.

It’s obviously a world-important topic, whatever your particular views on it. And this is about a good as a popular treatment of world population and trends in fertility than you could hope for: clear-headed, humane, careful. Similar vibe to Hannah Ritchie, who is quoted extensively.

Things I learned: globally speaking TFR has effectively always been declining since the first good records. Declining fertility is not a break in a trend; but passing from meaningfully above 2.0 to meaningfully below 2.0 nationally and soon internationally is and will be new, and marks the break from ~exponential population growth to ~exponential decline. Yes TFR is notably low in rich countries, but it not distinctive to rich countries. India is below replacement, China is well below at 1.00. I doubt I was alone in vaguely thinking population decline would reverse once high-fertility groups come to dominate the general population, i.e. the Amish will inherit the Earth. But, no, this is not at all given and looks empirically untrue. And finally we know very little about how to turn things around through public policy.

It is very, very salient how cautious Spears and Geruso are trying to be about the politics of population decline. As a topic it is so strongly associated with the political right, and (in the views of many) a particular kind of creepy, prying obsession with controlling women’s reproductive choices, continuous with trying to restrict access to reproductive healthcare and even contraception. The authors obviously don’t share these politics and (rightly) want to rescue the topic from its current political connotations. I am mostly very glad they are taking on that task, though given that I trust Spears and Geruso are not in fact prying misogynists, I might have preferred more focus on content and information and less of the defensive caveats and niceties.

It’s also notable how much population decline has in common with climate change as a social issue, given the very different cultural valences of the two topics to date. Both are problems of global and intergenerational public goods and bads; both problems of underincentivised externalities; both problems where poorer countries are largely exempt from blame; both problems where are choices today only really return to us decades hence.

The Passage of Power (The Years of Lyndon Johnson, #4)

Robert A. Caro (2012) • ★★★★★ • Sep 25 • Link to book ↗

LBJ was ruthless, just inhumanly tirelessly ruthless, in pursuit of power. That much is already clear from the first three volumes. But contemplating running in 1960, finally tasting the prize, the once calculated ruthlessness becomes frenzied and desperate. After accepting the vice presidency it manifests in his bitter rivalry with RFK, one of the great blood feuds of 20th c. US politics. And it’s all starker set against JFK the Ivy-schooled sophisticate, with his young sophisticated cabinet, an idealist whose legacy stayed mostly untarnished after that day in November ‘63. LBJ the sociopath; LBJ the bully.

“I’m just like a fox,” Lyndon Johnson once boasted. “I can see the jugular in any man and go for it, but I always keep myself in rein. I keep myself on a leash, just like you would an animal.” […] His ability to hurt had always been combined with a willingness—an eagerness, in fact—to put the ability to use; with a cruelty, a viciousness, a desire to hurt for the sake of hurting.”

And yet — the reason I expect Caro cared to write a book about this man’s life:

He was to become the lawmaker for the poor and the downtrodden and the oppressed. He was to be the bearer of at least a measure of social justice to those to whom social justice had so long been denied, the restorer of at least a measure of dignity to those who so desperately needed to be given some dignity, the redeemer of the promises made to them by America.

And yet:

By the time Lyndon Johnson left office [he] had become, above all Presidents save Lincoln, the codifier of compassion, the President who, as I have said, “wrote mercy and justice into the statute books by which America was governed.” And as President he had begun to do that writing—had taken a small but crucial, ineluctable, first step toward breaking the century-old barriers that, at the time he took office, still stood against civil rights on Capitol Hill—with that telephone call he had made to Representative Bolling on December 2, 1963 [to support the discharge petition]

More than once, the ruthless LBJ pushed ruthlessly for something more than self-interest; for the domestic legislation he’s remembered for. I had always guessed there was some cynical motivation — taking credit for work close to finished by Kennedy, or playing into overwhelming popular support. But it’s not true!

And of course the interesting possibility is that these two qualities were not always just in tension, but they needed each other; that you don’t pass bills through untouchable high-mindedness, that you need a bully on your side.

Caro you are the best to ever do it.

And the Roots of Rhythm Remain (ZE Series, 6)

Joe Boyd (2024) • ★★★★★ • Apr 25 • Link to book ↗

Boyd “was there when Dylan went electric, when Pink Floyd was born, and when Paul Simon brought Graceland to the world”. He’s a musical Forrest Gump, having apparently brushed shoulders with most of the legendary musicians that make up late 20th c. musical history, and having produced albums for a large handful of them. He says it took him 17 years to write this book; a big old quilt of political history, artist biography, personal anecdotes, and sheer music appreciation, loosely organised by chapter into region.

The effect is something like listening to your amiable, worldy, and obsessively knowledgable uncle reminisce while on a very long train ride. There isn’t really a point, how can there be, when each strand of “world music” is so sui generis, being more or less define by exclusion.

Instead it’s just endless and overlapping stories. Frank Sinatra getting his start from a chance meeting with an Buenos Aeries tango singer; João Gilberto playing alone on his guitar for days in a tiled bathroom until he emerged having invented bossa nova; a reporter tracking down the legendary wedding bands of Mauritania, who could never recreate their dazzling sounds in the studio. The stories are not just about “world” music, but the politics of music across the world: how often musical innovation came from fringe cultures and trading outposts; the repression of Balkan folk music and bizarre reappropriation of national song by the Soviets; and the Russian man who recalled hearing Rubber Soul’s ‘Girl’ by the banks of the Moscow river in 1974, thinking “whatever this music was, it represented the truth, so everything I had learned up until that moment must be a lie”.

The “world” (or “global”) musical label is a weird one; other genres also being terrestrial. Arguably “world” music is not a genre at all, Tuvan throat singing sounding no more like Ghanaian highlife than Western pop sounds like metal. What it is is a polite way of saying “styles of music not from English-speaking countries”. If you want to sell a compilation album of Bulgarian folk songs, or kora-playing Mande music, then (like it or not) the vaguely adventurous “world” label gives the Western consumer of music a touchpoint, a sham sense of familiarity.

Still, obviously Boyd thinks there’s more to it than that. At the end of the book he makes an analogy to biodiversity. Collectors and nature enthusiasts might care to preserve species for their own sake, but there’s more to biodiversity than fetishing nature: if you level a forest to grow the same variety of tree in neat rows, the artificial forest is more likely to wither and die.

Arguably, commercial musical culture has stagnated. So if English-speaking commercial music is a big river fed by new, unfamiliar tributaries, then it would suck if the tributaries totally dry up as a source of provocation and renewal.

On the other hand, isn’t that kind of patronising? What if “other” musical cultures want to steal the autotune and the digital metronomes from commercial music?

I went to a London concert by Abdel Aziz El Mubarak […] He opened with a beautiful slow taqsim, answering his vocal lines with slinky runs on the oud. Then he paused, looked over his left shoulder and nodded. The guy in the end chair pushed a button and the snap and thump of a beat box came blasting out of the PA speakers. The Sudanese cheered, raised their arms and began swaying from side to side; the rest of the audience exchanged glances. The records Charlie had been playing are driven by tarambouka hand drums, but now, on stage, the taramboukas were following the box. As more than a few White faces began moving towards the exits, the Sudanese looked at us in bewilderment: what's your problem?

So many musical genres are more new, more invented, less traditional, more a product of freely stealing from other sounds and newly splicing them together, than we care to realise. And when a genre gets big in the rest of the world, it’s often already become passé in its place of birth. The ‘roots’ of music are the sources of musical invention, not any ancient and unchanging musical traditions. The world should get its drum machines, so long as those roots remain!

Legal Systems Very Different From Ours

David D. Friedman (2016) • ★★★★☆ • Apr 25 • Link to book ↗

Friedman describes unfamiliar legal systems, and then makes sense of them in neat classical econ terms. It’s great.

Some of the legal systems examined are administered by a close-knit and mostly self-governing community within a larger society, such as the Amish. These communities cannot themselves threaten the use of state-backed violence, but they can and do threaten ostracism.

Interestingly, to the degree such smaller communities are tolerated by society at large, this makes defection more appealing and the threat of ostracism weaker, and so undermines those communities effective powers to enforce their own laws. Yet —

[T]he Amish have maintained their identity, culture, and ordnung, enforcing the latter by the threat of ostracism, despite the lack of any clear barrier to prevent unhappy or excommunicated members from deserting. Such desertion is made easier, in the Amish case, by the existence of Mennonite communities, similar to the Amish but less strict, which Amish defectors can and sometimes do join.

Also, it’s generally prohibited on international law that a state can just exile a citizen because they have broken its laws. I’m glad that’s an international norm, but it’s interesting to wonder why the line should be drawn at the level of states. The UN affirms the right to a nationality; and most democracies uphold a right to internal freedom of movement (states or provinces typically don’t have powers to ‘exile’). But there is typically no legal or political right to belong to an accepting community, which is presumably often just as important.

Most of the legal systems examined are generally more anarchic than “our” own. Typically if Annie commits a tort against Bob, then Bob can bring a civil lawsuit against Annie in the public court system. In practice, most tort cases do not reach as far as a formal trial, because Annie and Bob settle outside of court. That’s because the best alternative to a settlement is normally some (high) chance of damages, plus massive legal fees, stress, and time. There’s a range of settlements which look better to both Annie and Bob than the best alternative to negotiation, which is waiting for a trial and judgement, so Annie and Bob want to reach a bargain within that range.

This book is supposed to be about unfamiliar legal systems, but it got me thinking how much civil law takes place in private negotiations, with the threat of formal legal proceedings only looming in the background should negotiations fail.

Other legals systems extend this kind of “private law” further, in particular by extending it to criminal law, where defendants effectively have the option to bribe their way out of criminal punishment, and/or injured parties can effectively sue defendants directly for criminal damages. Per Scott Alexander:

Medieval Icelandic crime victims would sell the right to pursue a perpetrator to the highest bidder. 18th century English justice replaced fines with criminals bribing prosecutors to drop cases. Somali judges compete on the free market; those who give bad verdicts get a reputation that drives away future customers.

Something that makes courts seem pretty damn necessary is the threat of enforcement. PayPal can reimburse fraud victims, but it can’t punish fraudsters more than booting them off their platform. But the other useful function of courts is in discovering guilt in the first place, in cases where there’s information asymmetry between defendant and plaintiff.

As an aside, I’m curious why this process isn’t more privatised, at least initially in the case of low-stakes torts. If Annie (defendant) and Bob (plaintiff) can mutually trust a third party to (cheaply) anticipate the result of a trial, then they should agree to establish common knowledge of the result before going through the expensive process of a genuine trial. If Annie demurs, that is something like an admission of guilt, so she has a reason to cooperate just if there is some settlement better for her than her ultimate damages + legal fees and other costs. Maybe law people can explain this to me.

There’s a perverse efficiency to all this, of course. You might reasonably think law isn’t the place for efficiency, it’s a place for justice. If you’re Milton Friedman’s son, you’d cheerlead for efficiency too.

Engines of Creation: The Coming Era of Nanotechnology (Anchor Library of Science)

Eric Drexler (1987) • ★★★★★ • Mar 25 • Link to book ↗

Phenomenal. With a few exceptions, if you told me this book was written three years ago, I would have believed you.

The things that date the book are: where it makes rough decadal forecasts for nanotech breakthroughs, they are too aggressive. There is a patina of 70s/80s hard sci-fi, a world entirely shaped by the engineering frontier. Where the book imagines the opponents of the democratic world (or the US sphere of influence), the opponent is assumed to be the Soviets(!)

Amusingly, Drexler speculates about the still-frontier technology of “hypertext”, where one can load a reference listed on a digital document in mere seconds. Since this affords researchers such a vast speedup over working with libraries and copy machines, it offers hope for the world to competently navigate the challenges from nanotech and AI. There’s something charming and naive about piling up one’s hopes on (what became) the World Wide Web, but it is also very prescient.

There is also an amusing section about a book called Entropy: A New World View which proposes a (entirely bogus) “fourth law of thermodynamics” and predicts inevitable decline, recommending humans use as little useful energy as possible in the meantime.

Much of the second half of the book discusses how to strategise about reaching a safe, stable, and desirable world state once you have new tech that could destroy everything if you’re not careful. There are broad points of emphasis here which the AI safety discourse is only just re-appreciating.

This book basically articulates the worldview, with only minor modifications, of present-day transhumanism (and adjacent circles of AI-worriers and such). Maybe that is depressing (these communities are more intellectually stale than I thought), or just impressive on Drexler’s part.

Is nanotech discredited? The most feasible directions to get it are probably different from those described in the book, and it’s further away, technologically, than optimists might have hoped. The word ‘nanotechnology’ got co-opted as a kind of marketing term, giving the impression nanotech turned out to be a squib, so Drexler uses ‘atomically precise manufacturing’ or similar terms now.

The End of History and the Last Man

Francis Fukuyama (2006) • ★★★★☆ • Jan 25 • Link to book ↗

From the afterword:

Many of [criticisms of the book are] based on simple misunderstandings of what I was arguing, for example on the part of those who believed that I thought events would simply stop happening. I do not want to deal here with these kinds of critiques, which for the most part could have been avoided if the person in question had simply read my book.

Historical events did indeed keep happening and yet Fukuyama is underrated and basically vindicated. Notice that by the end of the 20th c., most countries on the planet either are actually liberal democracies, or else pretend to be democracies through sham elections and copying parliamentary institutions. Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, anyone? Democratic Republic of the Congo?

But the way Fukuyama argues the point involves a lot of Hegel and continental philosophy and mostly confused me. To a large extent I think we are just lucky that liberal democratic economies got richer faster than the alternatives in the 20th c., because planned economies didn’t work. And then I worry that AI undermines some of the forces that seem to push countries toward democracy. Let’s check back in after the singularity.

One Billion Americans: The Case for Thinking Bigger

Matthew Yglesias (2020) • ★★★★☆ • Jan 25 • Link to book ↗

Many people have a kind of deep-seated intuition that fewer people means higher living standards — if only (say) half the world volunteered not to have kids, the world would be less ‘overcrowded’ and we’d live within our planetary means, etc. This is actually a very good intuition to have under Malthusian conditions, which do (per Greg Clark) describe almost all human history before modernity!

A tragedy like the Black Death was a boon to survivors, significantly increasing wages in England […] Conversely, superficially good practices like superior hygiene in East Asia resulting in persistently lower rates of death by infectious disease created persistently lower living standards. These kinds of intuitions are deeply embedded in our psychology, and often excessively color discussions of population growth—particularly ones that muddy the waters between developing countries […] and modern technologically advanced service economies.

It is in fact an historically new and unfamiliar fact that growing a country’s population per se can leave everyone better off.

Otherwise, my main takeaway is that if you want to write a polemic with a shot at influencing policy, this is how you do it. The title is memorable and memeable. The headline proposal is insane-sounding enough to grab attention; and feasible enough to hold it. The arguments aren’t disingenuous but they are tuned to change unpersuaded minds rather than flatter the converted. (ironically this means One Billion Americans presents a case for immigration more tuned to appeal to conservatives than (the decidedly less progressive) Bryan Caplan’s Open Borders). It’s short, too, and hence recommendable.

Penance

Eliza Clark (2023) • ★★★★☆ • Jan 25 • Link to book ↗

Eliza Clark (real person) imagines a true crime novel by disgraced (fictional) journalist Alec Z. Carelli. Three teenage girls set their friend on fire in the seaside town of Crow-on-Sea (fictional) in North Yorkshire (real) on the eve of the Brexit referendum. The book mostly recounts the lead-up to that event: the friendships, resentments, and misunderstandings unreliably pieced together from interviews conducted by Carelli.

There’s so much here: the commentary on the seedy shamelessness of true crime; the details from 2010s Gen Z internet culture (Tumblr, Reddit, Insta); the shadow of British class and provincial politics; the pitch-perfect mean-girling dialogue of 2010s secondary schools.

In part, I read this as a book about conformity and pluralistic ignorance. There’s a scene where the characters are performing some kind of supernatural ritual, and one of the characters thinks to confirm out loud that it’s all just a bit of fun, then she considers how her friends will laugh at her for thinking they could possibly be serious, even if they were wondering the same thing, and she says nothing. See also the finding that “[most students] believed that they were more uncomfortable with campus alcohol practices than was the average student.” That pressure not to speak out gets ugly in the hands of adults with real power; but it surely peaks in the conformist hothouse of secondary/high school.

Japanese sociologist Ikuya Sato built on this in his 1991 book Kamikaze Biker, in which he examines the behaviour of Japan’s delinquent youth – specifically within the ‘bōsōzoku’ biker subculture. Essentially he posits that these youthful delinquents begin their careers merely playing at delinquency. They play the role of the violent biker – but, as Sato says: ‘The playlike definitions of the situation, however, cannot entirely keep playlike action from becoming serious’. That is – that the biker who ‘plays’ as the kind of a boy who might rob a stranger at knifepoint may find himself one day actually robbing a stranger at knifepoint.

2024

The Edge of Sentience: Risk and Precaution in Humans, Other Animals, and AI

Jonathan Birch (2024) • ★★★★☆ • Dec 24 • Link to book ↗

This is a strikingly consensus-building piece of public philosophy. I didn’t get much of a sense of Birch’s own hot takes — the book is more like an attempt to inform public policy in an extremely legitimate and reasonable-sounding way. So there are attempts to describe broad, agreeable-sounding principles of caution, and to draw big circles around zones of reasonable disagreement. It’s less coming from a ‘clear and coherent theory of ethics’ and more from ‘broadly appealing political theory’, which sounds like more of a dig than I mean it to be.

Two minor gripes: if you think the ‘edge’ of the capacity to feel pain is drawn (say) somewhere below birds and mammals, but above most invertebrates, then industrial animal farming is surely the worst thing humans are doing in the world, in terms of direct and ongoing harm. And presumably policy in rich countries is at least partly amenable to good philosophical arguments about sentience. But there wasn’t much discussion of factory farming at all, compared to topics like animal experimentation or ‘neural organoids’. I worry about zones of policymaking occupying more attention than factory farming (perhaps because they are newer and so less settled), despite being several orders of magnitude smaller in scale.

There was also a chapter on insects, arguing that (many) insects should be considered ‘sentience candidates’; that is, capable of feeling pain. That feels to me like it could be a staggeringly important fact about the world; but I felt a bit like Birch passed over (or even downplayed) the practical upshots. It’s true that humans don’t directly and deliberately harm insects in the way we do other vertebrates (e.g. through farming), but I worry about an implicit maxim which says we humans only have obligations toward creatures we own or directly expropriate.

So I found those parts a bit frustrating. But they only stood out because the substance of the book — especially the more sciencey parts — are very, very good. And the topic matters a huge amount. It’s quite dizzying to appreciate how ignorant we are about minds different from our own.

Dancing in the Glory of Monsters: The Collapse of the Congo and the Great War of Africa

Jason K. Stearns (2011) • ★★★★☆ • Dec 24 • Link to book ↗

On most counts, the deadliest conflict since WWII (including civilian deaths) is the 1998 Second Congo War. The figure is three million lives, at least through 2004. Estimates run over five million accounting for all conflict from 1996 to the present day. In terms of the lives it claimed, it surpasses Iraq, Vietnam, Korea, Afghanistan, Russia-Ukraine.

Like (presumably) most people, I knew close to nothing about the DRC and its history, and it gets very little airtime on western news. Perhaps for similar reasons: “NATO sent 50,000 troops from some of the best armies to Kosovo in 1999, a country one-fifth the size of South Kivu [one of 26 provinces in DRC]. In the Congo, the UN peacekeeping mission plateaued at 20,000 [ill-equipped] troops”

Unlike other conflicts, where there is often a clearer ‘opressor’ and ‘opressed’, or a single injustice to right; “[t]he Congo war had no one cause, no clear conceptual essence that can be easily distilled in a couple of paragraphs […] it is a mess of different narrative strands—some heroic, some venal”.

And when conflict in the DRC does show up in journalism or popular consciousness (in the west), Stearns complains about the attitude of morbid fascination, only “focusing on the utter horror of the violence” and portraying “an inscrutable and unimprovable mess”; ultimately too incurious or impatient to understand the politics.

There was an official ceasefire of sorts in 2002 but conflict is basically unresolved and ongoing. “[Survivors] didn’t have anything to help them address their loss […] The Congo is something of an outlier in this sense: Sierra Leone, Kosovo, East Timor, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia have all had tribunals to deal with the past.” It’s a history with frayed loose ends. (Indeed Stearns has a new book, The War That Doesn’t Say Its Name, asking why “the largest United Nations peacekeeping mission in the world and tens of billions in international aid” has still failed to end the fighting).

Not easy to get through (because the story itself is quite complicated, and because the events described are basically heartbreaking); but glad to have read this.

Abundance

Ezra Klein (2025) • ★★★★☆ • Dec 24 • Link to book ↗

Wow, what a hidden gem. If only it were more part of the discourse…

This book is a lightning rod for commentary. It is actually surprisingly short, but reviewing this kind of book is really a chance to talk about the scene it stands for — all the Substack posts and Twitter arguments and blog posts outside its pages.

Overall I think it is well-written and largely correct in the central argument (I strongly expected to agree with it and read it anyway; read into that what you will). Scattered thoughts below.

Most the book was written with a view to influencing a Democratic admin after 2024. It is squarely and explicitly calling out blue city and state government, and Biden federal policy. The planned publication date was summer 2024, in time to influence the DNC platform. Then, awkwardly, it got delayed and Trump won. So in the press circuit it is being spun as a playbook for how the Dems can win again in the midterms and 2028. But the abundance agenda is most persuasive as a theory about how to govern well, not which messages win elections. I have no idea if messaging around promises to deregulate housing and build green infrastructure etc. plays exceptionally well with voters. I hope it does, but the book doesn’t argue for that.

I wish the book pulled fewer punches. Noah Smith laments that “Klein has brought a gavel to a knife fight … Throughout their book, Klein and Thompson take great pains to specify that the goals of progressive obstructionism are good, and that they only disagree with the methods.”. The book is littered with phrases like “these are all worthy goals, but…” and this cedes too much ground. Some (especially municipal) governance goals are “worthy” in the most paper-thin of ways, and mostly just don’t work at all. It’s worth pointing this out.

I wish Klein and Thompson were harsher on the “degrowth” worldview. I might be misremembering, but I think they again praise the intentions but emphasise that it is politically unfeasible. No: if the degrowth worldview gained more of a foothold on the relevant regulation and planning policy (etc.), this would be straightforwardly bad. Abundance and degrowth are wrestling for the same levers. Abundance must make converts, not allies, of the degrowthers.

Smith also points out how one cluster of reactions reads Abundance as a kind of pro-corporate, pro-monopoly centrism, and critiques it in those terms. One story here is that among certain commentariat circles, Warrenite attitudes around “reining in big business”, and fighting back with more muscular antitrust, are very compelling framings and it’s hard to avoid interpreting this book in terms of them, even if the book doesn’t explicitly discuss these things very much at all. This is notable, though: maybe “fighting back against big corporations” just isn’t a very interesting framing here. If letting construction firms with a large headcount bid on a project, is that being “pro corporate”? Does this matter very much, if it leads to cheaper housing, or helps build solar infra, or whatever?

There is a section nominally about federal science grants, which focuses on healthcare. The argument is that discussions around how to distribute healthcare forget that the goods being distributed were invented and we can invent more of them if only e.g. the NIH grant process weren’t so baroque and risk-averse. One of the more interesting bits of Klein’s interview with Tyler Cowen was about whether this goes far enough, and whether a “true” abundance agenda wouldn’t be so shy about confronting the “healthcare as signalling” story.

Jason Furman (A+ account to follow on Goodreads) makes many good points, including that the book should have focused more on productivity growth in general, rather than housing + energy infra + (in effect) drug R&D, since TFP writ large matters more for wages. And also that, while yes we can push the production possibility frontier on these areas, still there will be some losers, and the book should be more explicit about that. This last point sounds right — see the “bat tunnel” fracas in the UK. The message here should not be that we can build bat-sheltering tunnels more effectively if only we make it easier to build; rather we should not build them at all, and something is going wrong in a process which mandates them. And this is because some things (like the opportunity cost of ~£100M) actually do matter more than other things (like marginally protecting a few hundred bats).

Lastly, I wish the book were 10% more angry. Klein and Thompson are so nice and temperamentally agreeable that you sometimes have to read between the lines to see the sheer stark absurdity of the subject matter. Outrage is the missing mood here, and I suspect it is a downplayed motivator for writing the book.

Political Order and Political Decay: From the Industrial Revolution to the Globalization of Democracy

Francis Fukuyama (2014) • ★★★★★ • Dec 24 • Link to book ↗

This is the second entry to a two-parter, the first being The Origins of Political Order: From Prehuman Times to the French Revolution. It’s an epic and basically successful attempt to write a sweeping political history of the world from the first states to the 21st century.

The key organising device was to think about societies in terms of state capacity, the rule of law, and accountability. ‘State capacity’ meaning something like ‘a bureaucracy to accumulate and administer the power of the state’. It can be efficient and well-organised; or corrupt, nepotistic, clientelistic. ‘The rule of law’ meaning some kind of judiciary, with some authority even over political leadership, and largely insulated from their whims. And ‘accountability’, meaning the decisions of the state (and the choice of leadership) are subject to correction by more or less of its subjects — basically, free and fair elections. For Fukuyama, ideal modern states (liberal democracies) score highly on all three counts.

But, when you think about it, it’s really not obvious how some societies got a relatively strong state, rule of law, and accountability. Beginning with an autocratic state, for instance, why would it ever ‘agree’ to subject itself to democracy and courts?

I liked these books because Fukuyama is not cherry-picking from history to illustrate his ‘one big idea’. He is trying to take political history in all its massive complexity, figuring out how to organise it in englightening ways, drawing out themes but noticing exceptions, showing connections and nicely insightful explanations for them, and mostly steering clear of sweeping, clever-sounding, abstract theses (a la Sapiens).

The analysis of the US as ‘vetocracy’ was especially good I thought. And despite his reputation as the ‘end of history’ guy, we get the right answer to “will more and more societies join the ranks of liberal democracy”, which is, “it’s complicated”.

The Enigma of Reason

Hugo Mercier (2017) • ★★★★☆ • Oct 24 • Link to book ↗

If a faculty for abstract reasoning is a ‘superpower’ for mapping out and navigating the world, then: (i) why are humans apparently the only animal capable of reasoning; and (ii) why are humans so often terrible at reasoning?

The proposed answer is that the (evolutionary) function of reasoning is to provide socially defensible justifications for beliefs and behaviors. W’re more interested in finding creative reasons which support our side than we are in finding reasons to switch side. On its face, this is a pessimistic theory: if reasoning is selfish, then why would anybody change their mind? Hence intractable disagreements on politics; unfalsifiable conspiracy theories; nobody gets ever smarter.

But there would be no point to giving justifications if anything goes: the flipside of giving reasons is being good at discerning good arguments from bad (since it’s selfishly useful to avoid being duped). Similarly, even if it pays to be a lying bastard as long as others fall for your lies, it also pays to discern others’ lies from honesty, and to change your tune if others catch you lying. Similarly, it pays to change your mind if your reasons for your beliefs are no longer socially justifiable.

So the takeaway isn’t that humans are terrible at reasoning; it’s more like “reasoning is more of a social than an individual phenomenon than you think”. Here’s a way to make sense of the ‘my-side bias’ we exhibit in arguing about some unsettled question: just how an economy is more productive if different people specialise in different trades, so a conversation is more productive if its participants specialise in defending a particular point of view they’re attached to and their identity is tied up with. Each individual participant might be irrationally stubborn, but (since accurate beliefs are never literally incoherent) the truth has an edge. Group deliberation is surprisingly effective!

4.5 stars.

On the Edge: The Art of Risking Everything

Nate Silver (2024) • ★★★☆☆ • Oct 24 • Link to book ↗

The ‘river’ and ‘village’ distinction is real and useful. Riverites are that crowd with outposts in EA / rationalist / Bay Area tech scenes; the kinds who go to house parties to argue with one another over music; Jacobins to the village’s cultural aristocracy.

Per Andy Masley, Silver gets the ‘avante garde EA’ crowd of people who care about some subset of AI risks, futurism, forecasting, and being borderline-obnoxiously analytical and quantitative about ethics. He gets it because, being a proud riverite, he’s more insider than outsider.

For narcissism of small differences reasons I found a lot of Nate’s commentary a bit annoying and superficial, and it’s too scattered to add up to much more than a bunch of journalistic sketches. Still, very readable.

Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks from the Stone Age to AI

Yuval Noah Harari (2024) • Sep 24 • Link to book ↗

I would be hard-pressed to tell you this book’s thesis, beyond “AI has to do with information” (which, ok) and “AI will be historically important”, which has been more pointedly argued elsewhere.

We also learn such insights as: AI could empower autocrats, but also it might not; accumulating more information sometimes helps people agree on what’s true but often it doesn’t; and the course of technological change is, to some extent, contingent.

Some of the more detailed historical sections were good — interesting for their own sake as much as they contribute to any structured argument — but ultimately this reads like big-idea history on a short deadline.

A Farewell to Alms: A Brief Economic History of the World

Gregory Clark (2007) • ★★★★★ • Sep 24 • Link to book ↗

There’s this great blog post, from Luke Muelhauser, called “Three wild speculations from amateur quantitative macrohistory”. Here is the nub:

I help myself to the common (but certainly debatable) assumption that “the industrial revolution” is the primary cause of the dramatic trajectory change in human welfare around 1800-1870, then my one-sentence summary of recorded human history is this: Everything was awful for a very long time, and then the industrial revolution happened.

This is Clark’s starting point. The task of the book is to explain perhaps the three most important features of long-run economic history:

(1) The ‘Malthusian’ era, in which subsistence incomes persisted throughout the preindustrial world (from settled agriculture to around 1800), despite better medicine and advancing scientific knowledge, owing to a coupling between fertility and income, plus a fixed trade-off between population and material income per person

(2) The Industrial Revolution — sustained and rapid economic growth, fueled by increasing production efficiency through advances in technology; and the demographic transition, a decline in fertility relative to income, translating the efficiency advances of the Industrial Revolution into a stratospheric rise in incomes per person (in much of the world);

(3) The ‘Great Divergence’, in which the efficiency advances and sustained economic growth triggered by the Industrial Revolution ended up very unevenly distributed across the world, such that income per person in the richest countries is around 100 times greater than those in the world’s poorest countries, who are today not significantly better off than before 1800 and in some cases worse-off.

The Malthusian era is the most counterintuitive but the best understood. It is really a kind of predictable default: (i) birth rates increase and death rates decrease as material living standards increase, and (ii) material living standards decrease as population increases (because there is less to go around, and because of dimishing returns to more labor holding other inputs fixed). The result (modulo short-term shocks) is subsistence — birth rates equalling death rates.

This gets counterintuitive: anything that makes life at a given income more deadly — poor sanitary practices, war, disease, etc. — increase the income required to maintain subsistence, so increase material living standards in the long run, and vice-versa. A technological advance — like a way to more efficiently grow crops — increase population size feasible at an income and income feasible at a population size. But assuming the birth and death rates as functions of income do not change, then the result is simply more people, not raised material standards of living.

Hence real income in Malthusian societies was fixed by birth and death rates alone, and then population size depended just on how many people a society could support at that income level given the available fixed inputs like land and production technology:

Jane Austen may have written about refined conversations over tea served in china cups. But for the majority of the English as late as 1813 conditions were no better than for [hunter-gatherers].

Yet there are no deep mysteries to this (from the modern perspective) upside-down world. Per Clark, “[i]n economics the known world thus stretches from the original foragers of the African savannah until 1800.”

The real question is how much of the world broke permanently free of the Malthusian regime, and got extremely rich in historical terms. Clark is good at knocking down popular single-factor explanations here, like the scientific institution-centric view of Joel Mokyr, the Protestantism/individualism-centric view of Henrich, or the ‘inclusive institution’-centric view of Acemoglu and Robinson. Contra Acemoglu and Robinson, Clark makes a pretty compelling case that all the institutional foundation-setting you could possible want was already in place centuries pre-1800. That is, to the extent it was in place at all around 1800, since the innovators in English textile manufacturing — surely those people most responsible for igniting the growth to come — were rewarded spectacularly poorly. And contra Henrich:

Protestantism may explain rising levels of literacy in northern Europe after 1500. But why after more than a thousand years of entrenched Catholic dogma was an obscure German preacher able to effect such a profound change in the way ordinary people conceived religious belief? The Scientific Revolution may explain the subsequent Industrial Revolution. But why after at least five millennia of opportunity did systematic empirical investigation of the natural world finally emerge only in the seventeenth century?

Clark’s own contribution to this question is to note how much did in fact incrementally change in the centuries preceding 1800. In particular:

Interest rates fell from astonishingly high rates in the earliest societies to close to low modern levels by 1800. Literacy and numeracy went from a rarity to the norm. Work hours rose from the hunter-gatherer era to modern levels by 1800. Finally there was a decline in interpersonal violence.

What accounts for the changes? On Clark’s story the clue is that not only do higher average incomes cause higher average birth rates in the Malthusian regime, but in preindustrial Europe and elsewhere, income correlated with fertility with society. “England was thus a world of constant downward mobility.” So whatever traits were associated with wealth came to proliferate over time, and the result a few centuries later is societies which are more stereotypically ‘middle class’ at all levels of society. And this quiet but significant change potentially explains why the preindustrial agrarian world needed to wait many centuries before an Industrial Revolution. In a sense, it wasn’t a revolution at all. It was a ‘spilling-over’ long in the making.

But that doesn’t explain why it did happen exactly when and where it did, nor why there was (apparently) a step change in the rate of growth at all. Nor is Clark as compelling on the causes of the demographic transition, though he has interesting suggestions.

As for the divergence in fortunes between post-industrial countries:

At a proximate level capital per person explains perhaps a quarter of income differences across countries in the modern world. But with capital free to flow across countries, and earning a rental that differs little across income levels, efficiency differences explain most of the variation in capital stocks. So at a deeper level efficiency differences are the core of the variation in income per capita across economies since the Industrial Revolution.

This claim is well evidenced but not well explained. Indeed the book seems to end a couple chapters early, and the bow is never really tied on the overall argument.

Still, this is a phenomenally insight-dense and non-patronising book (especially the dozens of tables of historical economic data that presumably took a bunch of grad students hundreds of hours to source). There is a version of this book which is more showily controversial and heteredox; I am glad Clark is more restrained than that:

God clearly created the laws of the economic world in order to have a little fun at economists’ expense.

Power, Sex, Suicide: Mitochondria and the Meaning of Life

Nick Lane (2006) • ★★★★★ • Sep 24 • Link to book ↗

Awesome. It takes some chutzpah to write a book about a tiny organelle and call it POWER SEX SUICIDE but the book lives up to the title.

Much to chew on, but here’s a question which stood out: bacteria haven’t become significantly more complex in billions of years. After all, they would need a larger genome to carry the extra information required to code for more complex functions, but extra genetic material is just costly baggage before it has nearly enough time to become useful. So there is in fact downward selective pressure on bacteria, toward simplicity.

Yet at some point eukaryotes happened, and they got a foothold. Cells became differentiated and organised together into big complicated multicellular organisms, their genomes increased in size; and this is the reason anything interesting happens.

But how? There isn’t really any cosmic force toward the complex; no ‘great chain of being’. We might imagine (as Lane does) that most ‘simple’ life in the universe simply gets stuck as bacteria-style sludge without ever hitting on multicellularity, sex, predation, and interestingness.

Whence complexity? The answer may shock you…

What Is Life? with Mind and Matter and Autobiographical Sketches

Erwin Schrödinger (1992) • ★★★★☆ • Sep 24 • Link to book ↗

The title essay is awesome. Striking how much we knew about genetic inheritance (recessive and dominant alleles, organisation of chromosomes etc) before the structure of DNA was known, and how well Schrödinger was able to anticipate the physical properties of DNA. Apparently Crick and Watson both credited the book for prompting their research.

The other talks and fragments are less exceptional.

Cognitive Gadgets: The Cultural Evolution of Thinking

Cecilia Heyes (2018) • ★★★★☆ • Aug 24 • Link to book ↗

At birth, the minds of human babies are only subtly different from the minds of newborn chimpanzees. We are friendlier, our attention is drawn to different things, and we have a capacity to learn and remember that outstrips the abilities of newborn chimpanzees. Yet when these subtle differences are exposed to culture-soaked human environments, they have enormous effects. They enable us to upload distinctively human ways of thinking from the social world around us.

This book is reacting to a bunch of nativist views in ‘high church’ evolutionary psychology, which claim that distinctively human patterns of thought are passed down through modern humans’ genetic firmware. Our firmware supposedly includes: instincts for social learning, like the ability and disposition to imitate others during development (maybe through ‘mirror neurons’?); a basic instinct for language, as in Chomsky’s universal grammar and ‘language acquisition device’; and a distinctive ‘mind reading’ module — some kind of innate ability to guess what other people are thinking and feeling based on how they act.

Then there’s the school studying ‘cultural evolution’. The big idea here is that (modern) humans set themselves apart by their ability to accumulate culture over generations, through being able to communicate complex new ideas (language instinct) and wanting to learn them (adaptations for social learning). We have all these “copy what works” instincts (like through selectively imitating elder or high-prestige group members), so the learning rate can win out against the forgetting rate across generations, so successive generations can build up complex cultures and technologies, so humans learn to hunt and make fire and farm and eventually smart fridges. See: The Secret of Our Success and The WEIRDest People in the World. This book is reacting to those views, or rather extending them.

Heyes agrees that modern humans are set apart, at least significantly, through the ability to accumulate culture via social learning. But culture runs deeper, she claims. The suggestion is that the enabling ‘instincts’ of cultural evolution aren’t part of the human genetic ‘firmware’, but are themselves learned and passed on through culture(!)

So we do not have hard-coded modules for theory of mind, or specific mechanisms of social/imitation learning, or a language faculty. Instead, we use more basic and domain-geneal faculties (like associative and operant learning) to boostrap distinctively human software.

For example, we are not (Heyes argues) born with a preinstalled faculty for knowing how to imitate the physical movements of other people. But adults like to imitate infants (e.g. doing an exaggerated smile if a baby smiles). So the infant, initially not knowing which motor commands correspond to smiling, learns an association between those commands and smiling, by watching adults. In turn infants are rewarded for imitating others, as in learning to walk, so they learn a disposition to imitate their own children, and the “cognitive gadget” of imitation is passed down as software, not firmware.

We know at least one very automatic and natural faculty which can’t have a dedicated module encoded via our genes: reading. Written language happened more recently than 10,000 years ago, which isn’t nearly enough time to install some kind of genetic “print reading” module. Instead, learning to read seems to borrow from relatively unspecialised brain real estate (the so-called ‘visual word form area’, which wasn’t used for reading in the ancestral environment).

So it goes for language, forms of social learning, and even theory of mind, on Heyes’ account. These are “gadgets” passed down by culture in much the same way “how to build a canoe” or “how to prepare berries” are passed down culturally.

Heyes writes in academese, so it’s often easy to miss how big these arguments are. Since cultural evolution is really only a phenomenon of modern humanity, the implication is that distinctively human “instincts” are really only innovations of the last 10,000 years or less. If this is true then (for example) theory of mind — being able to infer and empathise with what someone is thinking in any kind of sophisticated way — is <10,000 year-old invention, which our hominid ancestors significantly lacked. That is wild!

In other words: modern humans are less like specialised computers (entirely firmware, not easily programmable); and more like general purpose computers with a minimal operating system out of the box (you need to install the programs yourself). Programmable computers have this really key property that you can store and manipulate programs like data (see: ‘homoiconicity’). And for Heyes, programs, data, and programmable computers relate in the same way that “cognitive gadgets”, culture, and human minds relate. Humans pass on programs (“gadgets”) just like anything else, and then use those programs to learn and use and eventually pass on more stuff.

Is this good or bad news? The case for bad news is that cognitive gadgets are more fragile against catastrophe than instincts. If distinctively human gadgets are innate, then the next generation would rebound. If they are maintained by culture alone, they can vanish.

The case for good (?) news is that human minds are more pliable to big social/technological changes if more of our minds are software and less firmware than we thought. Heyes:

[T]he cognitive instinct view, famously implies that "our modern skulls house a Stone Age mind" (Cosmides and Tooby, 1997); in other words, the cognitive processes with which we tackle contemporary life were shaped by genetic evolution to meet the needs of small, nomadic bands of people, who devoted most of their energy to digging up plants and hunting animals. In contrast, cultural evolutionary psychology, the cognitive gadgets theory, suggests that distinctively human cognitive mechanisms are light on their feet, constantly changing to meet the demands of new social and physical environments. If that is correct, we need not fear that our minds will be stretched too far by living conditions that depart ever farther from those of hunter-gatherer societies. On the cognitive gadgets view, rather than taxing an outdated mind, new technologies—social media, robotics, virtual reality—merely provide the stimulus for further cultural evolution of the human mind.

Order without Design: How Markets Shape Cities

Alain Bertaud (2018) • ★★★★★ • Aug 24 • Link to book ↗

Two thirds of this book explains how modern cities grow and work — especially how housing prices and wages are set — from the perspective of urban economics. I learned a ton.

The other third is polemic. It’s polemic against the presumptions and overreach of planning — of overbearing land use regulations, buzzword-driven zoning laws, poorly motivated limits on building height and city extent. The morass in which “a creative zoning lawyer is far more likely to increase the profitability of a future building than a creative architect or engineer”, based on neither theory nor empirics but simply the “need to do something”. Seeing Like a State City.

Because Bertaud was a city planner, his arguments are more detailed and informed than you will ever read on (say) YIMBY-sympathetic corners of Twitter. The writing is kind of trim and restrained — more academic than argumentative. But it is lacerating.

Why do cities grow? The answer the book spells out is that cities are labor markets. Employers and employees want to move to where they can find the best choice of employees and employers, within their budgets. No functioning labor market, no city.

The effective size of a labor market is the average number of jobs reachable in a commute. So it can grow by increasing the distance reachable in a commute, or by becoming more dense (in terms of people per floor area and floor area per land). People seek out and benefit from larger labor markets.